Women's Emergency Corps

Women’s roles in the war effort varied from direct involvement as nursing sisters to indirect roles on the homefront as workers in factories. The Women’s Emergency Corps was charged with the organization of women on the home front. Initiated to counteract declining enlistment, their efforts were mandated by the government in order to persuade their men to enlist.

In January of 1916, the Parliament of Canada confronted a crisis of declining enlistment.[1] In an effort to encourage more men to enlist, they organized Emergency Corps of women throughout Canada. These groups were designed to encourage recruitment of men who had yet to enlist across the Dominion.

The initial organization in Brantford was dominated by men: J.M. Godfrey and M.E. B. Cutcliffe were two overseeing officials. The executive committee was populated exclusively by women, who were listed in the newspaper by their married names: Mesdames S. Alfred Jones, F.J. Bishop, W.S. Brewster, W.F. Cockshutt, James W. Digby, A.M. Harley, Lloyd Harris, N.D. Neill, Gordon Smith, George Watt, A.J. Wilkes and Miss Van Norman.[2]

At that time, the chief recruiting officer for Brantford and Brant County was Major Williams. He would regularly give sermons and ‘patriotic appeals’ to encourage enlistment of men in the area. Now that the Women’s Emergency Corps had been established, he made regular presentations to them as a means of encouraging their efforts. He emphasized the importance of using women’s networking abilities as a way of stimulating the enlistment of family members.

Encouraging women to seek employment in factories as a way to free up men was another strategy employed. The target was women who had never been in the role of ‘bread-winner’ and the method was to emphasize ‘doing their bit.’ The concept of sisterhood was also emphasized and women were encouraged to follow the example of their “English sisters and lending a helping hand in the manufacture of munitions of war.”[3]

The Brantford Expositor was enthusiastic in its support of women’s effort in the war: "our womenfolk have played well their part in the many spheres of action which have presented themselves." The newspaper reported on the work of Major Williams, whose job it was to educate women on the diversity of roles they could play, while not actively engaging in combat. Major Williams described the work of Red Cross nurses, then known as ‘Legionettes.’ He emphasized that the women of Brantford “make the greatest sacrifice of all by encouraging their loved ones to enlist for King and Country."[4]

Women’s level of patriotism and loyalty was weighed against their brothers.

“There are few shirkers among Canadian women. To them falls much of the sacrifice and suffering without any of the stripes and plaudits which come to much of those in khaki. Their ‘bit’ will never be forgotten, and there is not a man in Canada whose heart does not respond loyally to the sentiment: ‘The Women! God Bless Them!”[5]

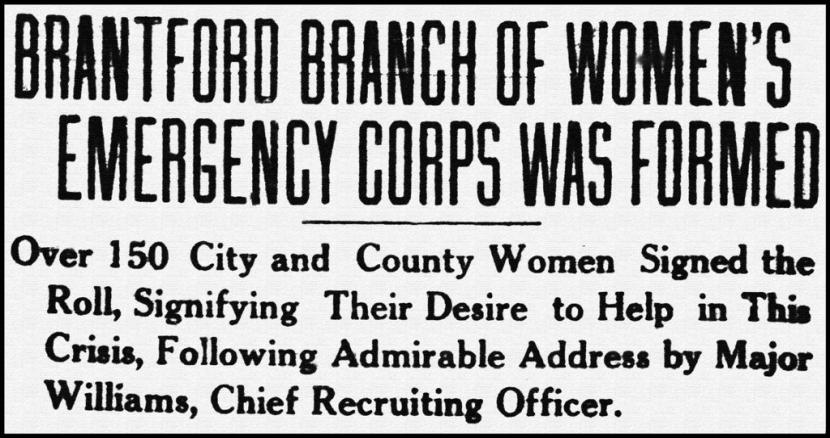

According to reports from The Brantford Expositor, Major Williams’ message did not fall on deaf ears. In his address to the women of Brantford at the Conservatory of Music in February of 1916, he continued to encourage the expansion of the Women’s Emergency Corps in the city. Both he and Mrs. Parsons (Principal Secretary of the Emergency Corps) spoke to a standing-room only audience. By the end of the event, approximately 150 women signed up to join the organization. Clearly, the work of the recruiting officer was having great effect in Brantford in its early stages.

According to reports from The Brantford Expositor, Major Williams’ message did not fall on deaf ears. In his address to the women of Brantford at the Conservatory of Music in February of 1916, he continued to encourage the expansion of the Women’s Emergency Corps in the city. Both he and Mrs. Parsons (Principal Secretary of the Emergency Corps) spoke to a standing-room only audience. By the end of the event, approximately 150 women signed up to join the organization. Clearly, the work of the recruiting officer was having great effect in Brantford in its early stages.

What was so important about this particular address was that Major Williams emphasized the special role women could play in the war. This was not a rallying cry for women’s liberation but was, instead, a call for women to step up and contribute beyond her "own social and home duties." He recognized that it was "not a time when women should be kept within bounds; there should be no limitations."[6]

In fact, the rhetoric used encouraged women’s separate, yet equal, participation in the war effort. He emphasized that women were demonstrating rather masculine qualities in the face of war: “we [the military] were proud to know of all the splendid heroism, hardiness and fighting qualities of the men in [this] great conflict, qualities which made them [women] the equal of the best soldiers in the world, and we should feel that no less truly, splendidly and bravely had the mothers done their part at home.”

The ultimate sacrifice of mothers who had given their sons did not go unnoticed and was recognized as a necessary feature in the war effort. “Their sacrifices were onerous, but they should not try to deter their sons from going.” In fact, preventing their sons, fathers and husbands from going to war was deemed unpatriotic and selfish. He argued, “women had, in the past, paid a great tribute, in spite of their constitutional weakness. They had drunk the deepest measure out of the cup of bitterness.”[7]

Major Williams laid out the two most important roles of women in the war effort, roles which would be emphasized and encouraged by the Women’s Emergency Corps. These were: a) to increase education about the gravity of the conflict, thereby increasing enlistment of men and; b) to ‘assist industrially’ by temporarily replacing men in the factories.

The language employed was often dramatic, inflammatory and crisis-laden. Williams predicted the ‘obliteration of the sweetest fruits of civilization’ if women did not participate in this effort. He also posed questions to tug at the heartstrings of the audience. When he asked “Would we like Canada to be like Belgium?” he was referring to the deplorable treatment of Belgians by their German conquerors. So important was the role of women in this effort to educate others and work in the factories that, if they did not take up this cause, the “Hun could come to our shore, could break through our nether line and our frontal line, there was nothing that could save us from degeneration.” It was women’s time to step up and do her bit to save civilization.

Mrs. Parsons was another person to speak and encourage the women of Brantford to act as educators and workers. She discussed similar events of the Women’s Emergency Corps of Dufferin County. She then went on to specifically target women in rural areas as “a great many women, especially in the country” were holding the men back. The old adage, “Men must work and women must weep” was argued against as Mrs. Parsons declared: “We [women] must keep the tears back. The fate of the Empire was in our hands. If we were to go down into history as the women of the day, we should do our duty by helping out the Emergency Corps.”[8]

Mrs. Parsons was another person to speak and encourage the women of Brantford to act as educators and workers. She discussed similar events of the Women’s Emergency Corps of Dufferin County. She then went on to specifically target women in rural areas as “a great many women, especially in the country” were holding the men back. The old adage, “Men must work and women must weep” was argued against as Mrs. Parsons declared: “We [women] must keep the tears back. The fate of the Empire was in our hands. If we were to go down into history as the women of the day, we should do our duty by helping out the Emergency Corps.”[8]

The sentiments of both Mrs. Parsons and Major Williams were repeated in a similar address in Burford later that same day. The equality of women was the first part of his message: “If there ever was a place they should be brought to an equal place with man it was in the present Great War.” Then, the rhetoric was ratcheted up as he stated that this was ‘not… a war between nations, but a war of God against the devil, of righteousness rising up on indignation against the worst of iniquity the world has ever seen.’[9]

Mrs. Parsons echoed these same themes by stating that “women [should] not be stumbling blocks in the paths of men, but to come out and take their places and let them go.” Again, the Belgian example was used to frighten the audience. Specifically, she focused on the story of three refugees, one of whom had his ears, the other his nose and the third her hands cut off. “Did we need something like that to happen here in Canada to waken us up?” For the recruitment team, complacency in war would be the death of liberty and freedom. While the message was clear, the Burford audience was less enthusiastic in response, with only one woman signing up for the Emergency Corps and only one new man attested after the event.

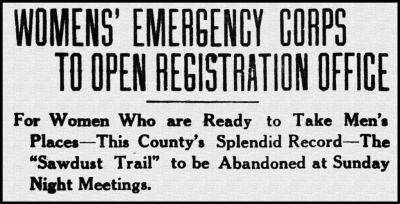

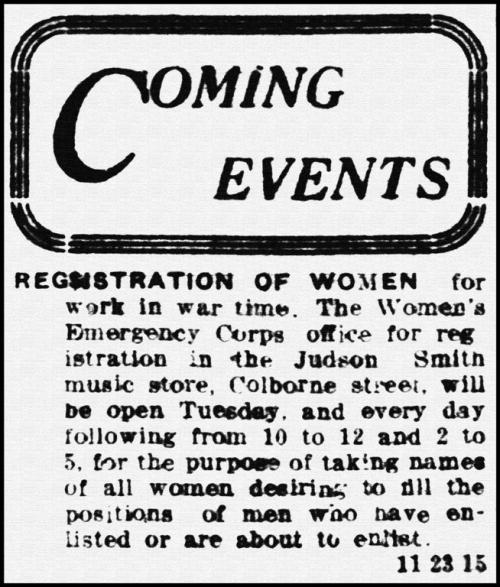

Local businesses also got behind the recruitment drive and showed support for the Emergency Corps initiative. Mr. Judson Smith allowed an office to be opened in his music store on Colborne Street which would be run by the Women’s Emergency Corps for the purposes of registering more women to ‘take the places of men who got to the front.’ This office was opened on March 14, 1916 from 10am-12 noon and then from 2pm-5pm. Miss Evelyn Buck was responsible for running the office. The Corps wanted to encourage women to fill the labour gap that the war had created. This work was never seen as permanent work and was referred to as ‘emergency work’ in a time of crisis. The office was established to create a list or ‘corps’ of women workers ready to fill the void.[10]

One criteria for employment was to have two references, including one from a medical doctor. The perception of women being less able to undertake manual labour was an issue prevalent in the employment of women at this time. They were often labeled as the ‘weaker’ or ‘fairer’ sex and there was frequent mention by employers who were concerned with women being able to handle long hours of work (for example: women in banks or factories where long hours of standing were required). To counter this concern, several women speakers advocated for women’s equal and consistent participation with men in the war.

Within a week of the initial opening of the office in Smith’s music store, 35 women had registered to take the place of men in the factories. Mrs. L. A. Hamilton, of Toronto, was brought in to emphasize the significant role of the Women’s Emergency Corps in the war effort and promoted the growth of the organization in the County of Brant – namely, Cainsville, Paris and Burford. She argued that all sectors of society should come together in the war – she urged a ‘consolidation’ of effort. She argued that all women should shoulder the burden of the war. This was not just something important in the war effort – it was necessary to build up the nation itself: “In this critical stage in the nation’s history it was clearly the duty of all womanhood to link itself together for an emergency … ‘on and on’ should be the slogan of every true, loyal Canadian woman.”[11] This unity could only be found in one organization – the Women’s Emergency Corps. Toronto was used as the benchmark by which Brantford could measure its success. Hamilton advocated that the City of Brantford and the County of Brant use a similar organizational structure as that which existed in Toronto.

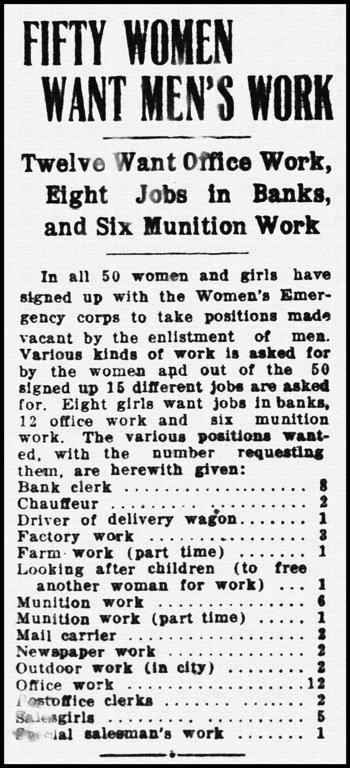

By the end of March, the number of women enlisted in Brantford increased to 50. The majority of women undertook office/clerical work. By April, similar organizations were appearing in other communities such as Cainsville, which operated a committee within their Women’s Institute.[12] In fact, this trend for the recruitment of women via the Women’s Emergency Corps even caught on in Burford and Paris where, earlier, the idea had been essentially ignored. By the middle of April 1916, a plan for the establishment of registration office similar to that in Brantford was in the works. Mrs. A.D. Muir was the President of the Burford organization, while Mrs. (Rev.) Plyley was President of the Cainsville operation and Mrs. D. Lovett was the President of the Paris organization.[13]

While the initial enlistment of women to these organizations for the purposes of work may not have been overwhelming, it did meet one of its mandates in increasing people’s understanding of the gravity of war and empowering women to encourage their men to leave the factory for the front.

[1] Canadian War Museum, “Voluntary Recruitment,” Canada and the First World War. http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/guerre/recruitment-e.aspx Date accessed: 19 May 2014.

[2] The Brantford Expositor, January 8, 1916.

[3] The Brantford Expositor, January 27, 1916.

[4] The Brantford Expositor, February 2, 1916.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Brantford Expositor, March 14, 1916.

[11] The Brantford Expositor, March 17, 1916.

[12] The Brantford Expositor, April 8, 1916.

[13] The Brantford Expositor, April 11, 1916.