Six Nations Support of WWI

Although Six Nations did not officially declare war, they still supported the war effort through monetary donations, fundraising campaigns, and the making of soldiers’ comforts, like socks, scarves, and mitts. Whether they rallied because of their patriotism to, or their allied status with, the British Crown, the Six Nations played a significant role, especially when it came to supporting their soldiers at the front.

Although the Grand River Six Nations did not officially declare war, due to their understanding that they were allies and not subject to Britain, they still supported the war effort, especially their soldiers. By November 1914, they had formed their own Patriotic League. The Six Nations Confederacy Council granted them $50.00 to purchase yarn to knit socks for Six Nations soldiers.[1] The proposal to grant funding to the Six Nations Patriotic League was at first rejected by the Confederacy Council during their meeting on November 3, 1914. The cause was that the proposal had been presented to the Council by non-Six Nations people, namely Rev. Edmunds, a Methodist missionary within the Grand River Territory and Dr. Walter Davis. This went against the Confederacy Council’s protocols, as the person or group asking for money from the Council had to be a member of Six Nations. Once it was proposed to the Council by women from the Six Nations Patriotic League, the money was granted.[2] By November 26, the League had produced and shipped three dozen pairs of socks overseas through the Canadian Patriotic Fund.[3]

Although in full support of the war, the Six Nations Patriotic League was not immune from discrimination. In 1915, on the orders of the Department of Indian Affairs, knitting for soldiers overseas was stopped due to fears that small pox was known to exist within the Territory. The Department was concerned that the disease would be spread to the soldiers once they received the socks. At the time of this ban, more than fifty pairs of socks had already been knitted, which were later distributed throughout the Territory so as not to go to waste.[4] A month after the ban was put in place, Evelyn Davis, a member of the Six Nations Patriotic League, wrote to the Department of Indian Affairs claiming that the Six Nations women of St. Peter’s Church had 100 pairs of socks ready to be shipped. She further claimed that this ban was discriminatory against the Six Nations as there were areas of Brantford and other communities that were known to be infected by small pox and they were still allowed to knit and ship socks overseas to soldiers.[5] Soon after this letter was written, the ban was lifted.

Some Six Nations women also made quilts for the Belgian Relief Fund.[6] These quilts, along with other comforts for soldiers, were sent overseas by various patriotic groups within the Territory. Other comforts included wristlets, mittens, cups, helmets, khakis, silk handkerchiefs, chocolate, fruitcakes, Christmas puddings, tobacco, writing paper, and clothing for orphaned children.[7] The only time the Six Nations Confederacy Council refused to grant money to the Six Nations Patriotic League was in December of 1916 as there was no record of Six Nations men ever receiving socks from the Council’s first grant.[8] It is not known whether an accounting for the socks was ever provided, but the Council continued to grant the League money throughout 1917 and 1918. Through available records, it is clear that the Six Nations Council gave the Six Nations Patriotic League anywhere from $350-$415 in grants, which was added to the money raised by the League through private donations and fundraisers.[9] All of this money was used by the Six Nations Patriotic League to buy wool for the making and purchasing of comforts for soldiers. Due to the existence of their own Patriotic League, the Six Nations Confederacy Council refused to grant money to other pro-war charitable organizations from surrounding communities.[10]

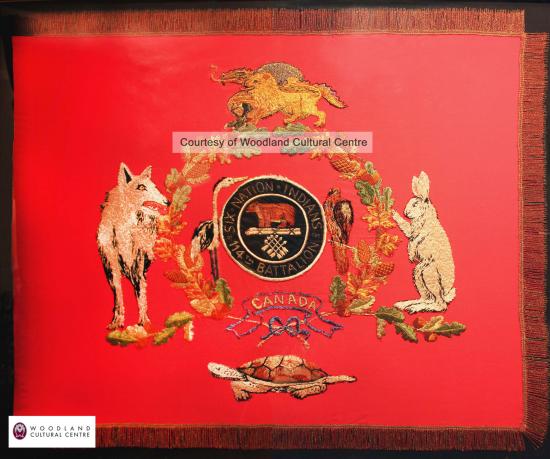

Further evidence of the support that the Six Nations Patriotic League provided for their soldiers can be found in the fact that the League lobbied the Canadian government for special dispensation to create and present the 114th “Brock’s Rangers” Battalion with a hand-stitched regimental flag during a public ceremony in Caledonia. Since the regiment was heavily recruited from the Grand River Territory, and D Company and the regimental band of the 114th battalion were not only made up entirely of Six Nations men, but also housed and trained within the Grand River Territory, the flag contained traditional Six Nations symbols side by side with symbols that represented the British Crown.[11] According to the Woodland Cultural Centre, which now cares for and displays the flag:

“The flag shows five clan symbols: the wolf, the eagle, the heron, the turtle and the bear. The turtle is situated at the base to symbolize the earth, Turtle Island. The bear clan is in homage to the first great warrior, Joseph Brant. His Mohawk name is Thayendanegea, meaning two sticks bound together, denoting strength, thus the image in the centre which represents a war shield. The six arrows signify the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, Mohawk, Cayuga, Seneca, Tuscarora, Oneida, and the Onondaga Nation. The oak leaves and acorns symbolize life and sustenance from the Creator and the white pine the symbol of the Great Tree of Peace given to the Six Nations by the Peacemaker in the creation of the Great Law. The dragon and the lion are symbols for the Crown. The white hare is unidentified but is believed to symbolize the Ojibwe who were also members of the 114th Battalion.”[12]

Six Nations scholar Rick Hill has also noted that the centre crest in the flag, with the bear and the arrows, was the original seal of the Six Nations Confederacy Council.[13] The Six Nations Patriotic League also commissioned a mahogany flagpole for the flag, at the top of which was a bust of Joseph Brant. The bust was modeled after a portrait sent by the Duke of Northumberland and was completed by Mr. Earle who had emigrated from Glasgow to Canada.[14] (http://tomorrow.is/news/six-nations-hunt-lost-world-war-history/#.U-0Dxk...)

In addition to the support detailed above, the Six Nations Confederacy Council contributed to various war funds. In 1914, the Six Nations Chiefs extended the offer of $1,500 and their warriors to the British as a token of their alliance.[15] The Department of Indian Affairs intercepted and responded to this request, claiming that the Six Nations could not send the money directly to the British, but it could be given to the Canadian Patriotic Fund.[16] This offer, according to the Six Nations Visiting Superintendent Gordon J. Smith, was unacceptable to the Six Nations as they did not believe themselves to be part of Canada and therefore wanted the money to be given directly to Britain.[17] It seems unlikely that the money in question was ever passed on to the British.

In 1917, the Six Nations sent lawyer A.G. Chisholm to purchase $150,000 in war bonds.[18] Further, in November 1917, the Six Nations Council authorized the Department of Indian Affairs to invest any and all money from their Trust Fund into Canada’s Victory War Loan for a period of five years.[19] The Six Nations Trust Fund was a fund that was set aside for the Six Nations by the British Imperial government. The fund was to act like a bank account: the Six Nations were to put all their money from the lease or sale of their land into it. This money was not only supposed to grow in value due to interest, but the Six Nations were to have access to it if ever they needed it. In reality, the funds were much less fluid; they were to be held in trust by the British, and later the Canadian government. If either of these governments did not like the reason Six Nations were asking for money, they could reject the request. It appears that both the redirection of trust fund monies and the purchase of $150,000 in bonds were rejected by the Canadian government, as only one donation of $50 appears in the Department of Indian Affairs accounting of Six Nations wartime donations during and after the war. This single donation is said to be from Six Nations Patriotic League, not the Six Nations Confederacy Council.

According to a 1917 accounting of their war donations, the Six Nations Confederacy Council gave about $1,700, which did not include the money offered by the Six Nations Council to the Victory War Loan campaign in November of 1917.[20]

GWCA Search for Lost Artifacts:

Known for their expert knitting, the GWCA is currently looking for any information or photographs about knitting and other sewing patterns from Six Nations Patriotic League. If you have any information about these or any other Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations First World War artifacts or photographs, we would love to hear from you! Please e-mail us at info@doingourbit.ca.

[1] Six Nations Council Minutes for November 17, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 3015, File 218,222-178, Reel C-11311, Six Nations Agency – Minutes of Council Meeting held Between 3 and 17 November Respecting Sundry Matters).

For more information on Six Nations women’s work during the war, see Alison Elizabeth Norman, “Race, Gender, and Colonialism: Public Life Among the Six Nations of Grand River, 1889-1936” (Ph.D. diss., University of Toronto: 2010) and her article, “‘In Defense of the Empire’: The Six Nations of the Grand River and the Great War,” in A Sisterhood of Suffering and Service: Women and Girls of Canada and Newfoundland during the First World War (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012).

[2] Six Nations Council Minutes for November 17, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 3015, File 218,222-178, Reel C-11311, Six Nations Agency – Minutes of Council Meeting held Between 3 and 17 November Respecting Sundry Matters).

[3] Letter from Duncan Campbell Scott to M.A. Brown (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509, War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[4] Letter from M.A. Brown to Duncan Campbell Scott (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[5] Letter from Evelyn Davis to M.A. Brown (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[6] Letter from Evelyn Davis to M.A. Brown (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[7] Brant Aryan Society, Report of the Aryan Society and of the Six Nation Indians Women’s Patriotic League, County of Brant (Brant Aryan Society, 1916), 17.

[8] Excerpt from the Six Nations Council Minutes from December 7, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[9] Excerpts from varying Six Nations Council Minutes (RG 10, Vol. 6763, File 452-5 Part 1, Reel C-8509 War 1914-1918 – Correspondence Regarding Funds Awarded to the Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League for Knitting done for Indians Overseas).

[10] Excerpt from the Six Nations Council Minutes from May 2, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 6762, File 452-2 Part 2, Reel C-8508 Contributions from Indians to War Funds) and Excerpt from the Six Nations Council Minutes from October 10 and November 9, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 6762, File 452-2 Part 3, Reel C-8508 Contributions from Indians to War Funds).

[11] Warriors: A Resource Guide (Brantford: Woodland Indian Cultural Education Centre, 1986), 20 and The Brantford Expositor, September 13, October 3, and October 4, 1916.

[12] Museum label from Woodland Cultural Centre.

[13] Richard W. Hill Sr., War Clubs and Wampum Belts: Hodinohso:ni Experiences of the War of 1812 (Brantford: Woodland Cultural Centre, 2012), 82.

[14] The Brantford Expositor, May 25, 1920.

[15] Excerpt form the Six Nations Council Minutes from September 15, 1914 (RG 10, Vol. 6762, File 452-2 Part 1, Reel C-8508 Contributions from Indians to War Funds).

[16] Letter from Duncan Campbell Scott to Gordon J. Smith September 21, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 6762, File 452-2 Part 1, Reel C-8508 Contributions from Indians to War Funds).

[17] Letters from Gordon J. Smith to Duncan Campbell Scott September 26, October 14, and October 26, 1916 (RG 10, Vol. 6762, File 452-2 Part 1, Reel C-8508 Contributions from Indians to War Funds).

[18] Letters from Duncan Campbell Scott to the Six Nations March 28, 1917 (RG 10, Vol. 3195, File 492-946, Reel C-11338 Six Nation Agency – Investment by the Band in War Loan Bonds).

[19] Six Nations Council Minutes from November 27, 1917 (RG 10, Vol. 1741, File 63-32 Part 8, Reel C-15024 Minutes of Six Nations Council – Six Nations 1917-1918).

[20] Six Nations Council Minutes from May 2, 1917 (RG 10, Vol. 1741, File 63-32 Part 7, Reel C-15024 Minutes of Six Nations Council – Six Nations 1916-1917). This is the figure that the Six Nations Council came up with in May 1917. More money could have been given or offered by the Council from this point to the end of the war.