Women in Industry - Brantford and Brant County

The Great War had a profound effect on the role of women, whether at the front, in factories back home or in charitable organizations. As more men were called to the front, increasing numbers of women were taking their places in the factories of Brantford and Brant County. It is important, however, not to see these women through the lens of contemporary expectations. They were keen to support their men and perfectly aware that they were temporarily replacing those who had gone to fight. While women remained masters of the domestic sphere, they were also beginning to envision an expanded role in the public domain as well.

In the early years of the war, gender roles remained largely unchallenged and women were not used extensively in industry. Initially in 1916, the placement of women in factories was seen as a last resort. Between August and September of that year, it was reported that the ‘fair sex’ was not actively seeking employment. Brantford industrialists saw the employment of women as a ‘step having to be made’ out of necessity, but not out of any desire to increase women’s employment as a part of an equity platform.

In the early years of the war, gender roles remained largely unchallenged and women were not used extensively in industry. Initially in 1916, the placement of women in factories was seen as a last resort. Between August and September of that year, it was reported that the ‘fair sex’ was not actively seeking employment. Brantford industrialists saw the employment of women as a ‘step having to be made’ out of necessity, but not out of any desire to increase women’s employment as a part of an equity platform.

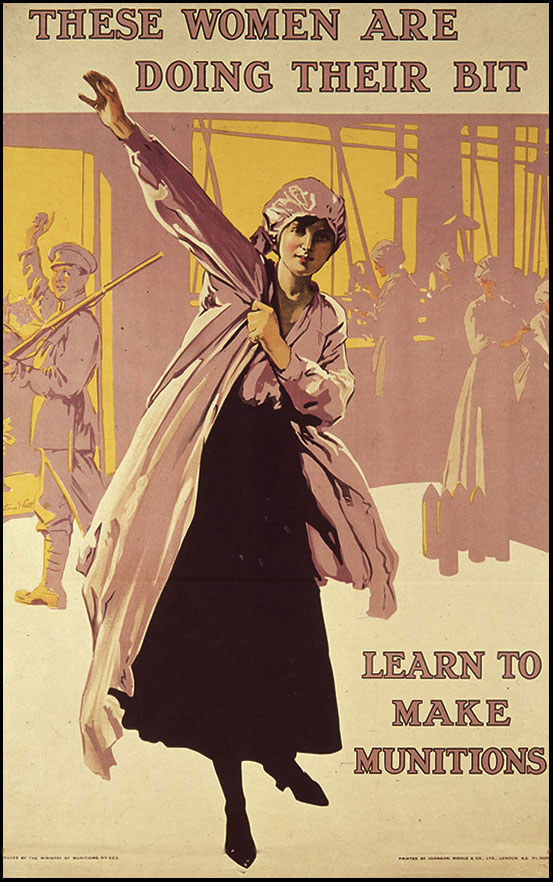

However, by 1917, the employment of women in the industrial sector had increased significantly and so had the use of gender equity rhetoric to encourage women to ‘do their bit.’ In fact, when rumours had "circulated throughout the Teutonic nation" that there was a lack of munitions amongst the Allied nations, The Brantford Expositor bragged about women who had "risen to the occasion with remarkable, even wonderful heroism, inspired by a sense of duty." Women were responsible for manufacturing "death-dealing" shells and were working "coast to coast in practically every munitions plant."[1]

Women’s involvement in the industrial sector was so ingrained by 1917 that feminizing language was being used to describe woman’s work – they were munitionettes, farmerettes, and inspectorettes. They were no longer ‘temporary workers’ but permanent members of Brantford labour. Women felt that their participation in industry was a natural substitution for fighting on the front. One woman worker from the Brantford Computing Scale Company pleaded, “it is impossible for me to go in the trenches, so I am doing the next best thing. My only regret is that I cannot do more.” Quotes by women were even used to publicly shame men who had not signed up for the war – the shirkers. The girl from the factory on Grey Street also stated “… I intend to stick it out as long as my country needs me. If more of the men felt as I do about this war there wouldn’t be so many shirkers around the streets.”[2] This enthusiasm for the war effort was rewarded with the franchise – according to news reports.

By late summer and early fall of 1917, the first factory to employ women in a wartime industry – Brantford Computing Scale Company – shut down its munitions sector. Both women and men were laid off. While women were starting to be accepted into the industrial front not all work was deemed suitable for the ‘gentler sex.’ Even while some local businesses sought to employ of women workers within Brantford, one woman was flatly refused the job of ‘baggage-smasher’ at the Grand Trunk Railway Station. Despite the fact that she was described as ‘well-built’ and demonstrated ease in lifting heavy items – the officials "could not see a woman handling baggage, even if men were scarce."[3] Even though women were needed on the job, they were not always deemed suitable for the job because of their gender.

While women’s involvement in the labour force increased, so did calls for them to unionize. Women were willing to work hard and often worked very long hours doing jobs that had traditionally been done by men in the industrial sector (e.g. munitions workers). In a letter to the editor of The Brantford Expositor in October 1917 (during the same month as the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia), Mrs. Kite urged women to unionize – “Girls! Why not organize and place yourselves in a position to demand your rights? A shop employees’ union would soon solve the problem of shorter hours…. band yourselves together to work with those who are already striving by organization to better their conditions and to usher in that day.”[4] The letter is bookended by familiar English literature – introduced with lines from Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village” (1770) and closed with a part of the Rudyard Kipling poem, “After Earth’s Last Picture is Painted” (1892) –

When no one shall work for money,

And no one shall work for fame;

But each for the joy of working,

And each in his separate star

Shall do the thing as he sees it

For the God of things as they are.

Near the end of the War, The Brantford Expositor specifically highlighted the industrial contributions of women in factories throughout the city. On October 26, 1918 the ‘weaker sex’ were touted as holding their own with the men. The lengthy article highlighted women’s work in the Kitchen Overall Factory, Steel Company of Canada, Motor Trucks, and Brantford Canning Factory. Women were described as having an equal role in the war effort – “The Canadian girl has learned to make the ball the Canadian boy shoots. If it fails a ‘dud’ the girl at the machine shares the blame; if it clears its spot in the trench for the army’s advance, with the girl at home the soldier divides the glory.”[5]

The nature of women’s work, from hours to working conditions, was predetermined. Specifically, the importance of a ‘matron’ to look after the women workers was emphasized. That women were hired to oversee the work of other women is a significant point. The matron was hired to ensure that the physical strength of the ‘weaker sex’ was maintained. She tended to the women by taking their temperatures, ensured that the women took appropriate breaks, administered First Aid and oversaw nearly 40 ‘girls’ at any given time. Mrs. Little was given as an example in the Steel Company of Canada and Mrs. W. G. Oxtaby was hired as the matron at Motor Trucks. This all coincided with the Spanish Influenza of 1918. The matron’s role became doubly important to protect women’s health generally, and to prevent the spread of disease amongst their group (by spreading disinfectant throughout the apartments).

Specific jobs held by women workers were described: some were metal moulders, others ran grinders, and some were hired by the government to perform quality control using a set of gauges to measure every shell. Some workers’ jobs were described colourfully as giving the "finishing touch" to the "monsters of destruction" whereby the girls would paint the shells with enamel. Up to 2000 shells were cased for shipment per day and each of those shells would pass through the hands of the 40 girls in the factory. In terms of wages, women were paid through piece-work.

At Motor Trucks it was exclusively the job of women to inspect materials being produced. But, the factory was being outfitted to accommodate for more women workers on the production line. In order to train the women quickly, there were special ‘Schools of Instruction’ in which women were to be taught by other women how to do the job on the line at Motor Trucks. Women and men worked separately in some instances took breaks in separate locations and ate in different lunch rooms. It is important to note that in all instances of women’s work, they are described as ‘girls’ while male workers were described as ‘men.’

The concern about women replacing men in the workforce was not often discussed as the expectation for women was to return to the home as soon as the war ended. The manager at Brantford Canning factory, where women were starting to run machines formerly run by men, noted that women workers were difficult to keep because ‘as soon as laddie boy come home, wifie will leave too.’[6]

The concern about women replacing men in the workforce was not often discussed as the expectation for women was to return to the home as soon as the war ended. The manager at Brantford Canning factory, where women were starting to run machines formerly run by men, noted that women workers were difficult to keep because ‘as soon as laddie boy come home, wifie will leave too.’[6]

Women were actually seen as assets in one job sector – banking. In an anonymous survey of male bankers in Brantford, one gentleman ‘found them smart, accurate, willing to work anytime, better bookkeepers, better writers than the boys.’[7] He was so impressed with the quality of work his female employees did that he proclaimed that he would rather have women workers than men. The Brantford Expositor reported that “he imagined his girls were not the rule but a great exception.” So, while he was impressed with the work he didn’t see it as a reflection on female workers generally. This attitude was echoed by some other managers, but they also placed limitations on what women were able to do as the ‘fairer sex.’ One manager argued that his ‘girls’ should not be allowed in the teller’s cage because long periods of standing might cause a "big nervous strain." Yet, when it came to whether or not these women would ever climb the ladder to become a supervisor or manager, there was a resounding resistance because "the idea had not occurred to them before." The Brantford Expositor reported: “The top rung of the ladder was still reserved for the male sex, although the consensus of opinion votes the girls neater, more accurate, and more painstaking.”[8]

Brantford’s largest industry was the agricultural implements sector – with Massey-Harris being one of the largest employers of women in that field. By late 1918, there was even a separate entrance for women workers, which was labelled clearly with a large sign that hung across Market Street. By October 15, Massey-Harris had been employing young women who worked throughout the nine different departments. Again, a matron was hired to oversee female workers: Miss Wisener’s job was to watch over their ‘welfare and behavior.’ It is interesting to note that the purpose of the female supervisor was to provide maternal guidance and ensure that the work environment was to reflect a ‘family.’ So, while women had left their homes, the maternal role was still echoed in the workplace.

Many of the women who worked at Massey-Harris during the war were described as being “soldiers’ wives,” but again were highlighted for their valuable work they provided. One woman was in charge of three separate machines and had to run between them. She was described by her female supervisor as "one of the best workers." In fact, the ‘family’ atmosphere of the factory was further emphasized in a passage describing the work of women and children in the ‘Nut and Bolt’ rooms: “One girl kept a big machine fed with nuts, and the monster’s appetite was insatiable. A little boy and little girl were sitting at the table across from each other screwing nuts onto bolts like two little machines.”[9] Further on, a comment was made which demonstrated the characteristics of Total War in an industrialized nation: “An idea of the number of human cogs in the big works was slowly impressed on one in the progress through the factory. Every minute part meant a different individual to supply it.”[10]

Many of the women who worked at Massey-Harris during the war were described as being “soldiers’ wives,” but again were highlighted for their valuable work they provided. One woman was in charge of three separate machines and had to run between them. She was described by her female supervisor as "one of the best workers." In fact, the ‘family’ atmosphere of the factory was further emphasized in a passage describing the work of women and children in the ‘Nut and Bolt’ rooms: “One girl kept a big machine fed with nuts, and the monster’s appetite was insatiable. A little boy and little girl were sitting at the table across from each other screwing nuts onto bolts like two little machines.”[9] Further on, a comment was made which demonstrated the characteristics of Total War in an industrialized nation: “An idea of the number of human cogs in the big works was slowly impressed on one in the progress through the factory. Every minute part meant a different individual to supply it.”[10]

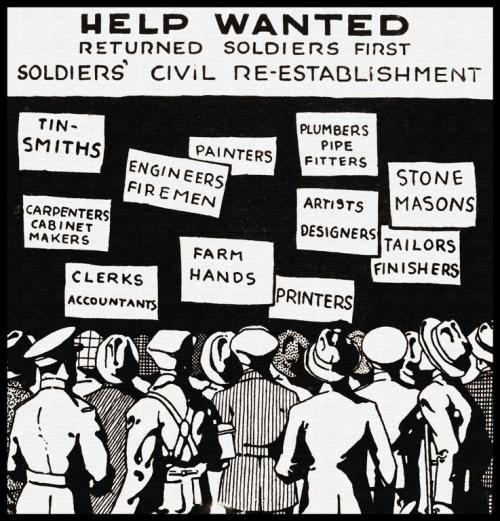

Once the war finished, so did women’s work in industry. By January of 1919, Motor Trucks had no female workers and at the Steel Company of Canada there only remained two female workers. At Massey-Harris, because the industry was consistent in one area (agricultural implements vs. munitions), there were more women who stayed on and “there was no attempt to replace them with men, yet…. [as] many of them are married women and they are industrially necessary.”[11] The expectation was that if men could work, then they should so that women could return to their homes.

[1] The Brantford Expositor, March 13, 1917.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The Brantford Expositor, October 2, 1917.

[4] The Brantford Expositor, October 19, 1917.

[5] The Brantford Expositor, October 26, 1918.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] The Brantford Expositor, November 23, 1918.

[10] Ibid.

[11] The Brantford Expositor, January 21, 1919.