Loyalty to the Crown

Greeted by the people of the Brantford as city wide holidays, Royal visits to the area re-connected its citizens to the wider British Empire which they had served from the settlement’s early days to the First World War. For the Six Nations, however, Royal and Vice-Regal visits were more than patriotic celebrations, but a time for the Six Nations and the British Crown to revisit their alliance, which began with the Two Row and the Silver Covenant Chain Wampum, also known as the Friendship belt, in 1667. Although these visits were celebrated for different reasons, the people of Six Nations and Brantford and Brant County shared a loyalty to the British Crown before, during and after the First World War.

Patriotic celebrations were common in Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations, whether it be celebrating royal weddings,[1] the end of the Crimean War,[2] or Bread and Cheese Day.[3] For the citizens of these communities, Royal visits gave a face to their community’s link to the British Crown. For the people of Brantford and Brant County, Royal visits connected people to the British Empire, reinforcing their identity as United Empire Loyalists who came to the area to settle after the American Revolution. For the Six Nations, Royal visits were celebrations, but also a time for the Six Nations to commemorate their alliance with the British Crown. When the Six Nations entered into an alliance with the British through the Two Row and Covenant Chain Wampum, it dictated that, not only were the Six Nations and the British allies, but they were equal and separate nations. The Silver Covenant Chain (1667) was a diplomatic devise that solidified a military, political and economic alliance between the Six Nations and representatives of the British Crown. It dictated that the two parties would meet frequently and “polish” the relationship between them so it would always shine and never tarnish. When British Royalty or Crown representatives came to visit the Six Nations, the Six Nations took the opportunity to remind the British of their alliance and anything that might be “tarnishing” it.

Patriotic celebrations were common in Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations, whether it be celebrating royal weddings,[1] the end of the Crimean War,[2] or Bread and Cheese Day.[3] For the citizens of these communities, Royal visits gave a face to their community’s link to the British Crown. For the people of Brantford and Brant County, Royal visits connected people to the British Empire, reinforcing their identity as United Empire Loyalists who came to the area to settle after the American Revolution. For the Six Nations, Royal visits were celebrations, but also a time for the Six Nations to commemorate their alliance with the British Crown. When the Six Nations entered into an alliance with the British through the Two Row and Covenant Chain Wampum, it dictated that, not only were the Six Nations and the British allies, but they were equal and separate nations. The Silver Covenant Chain (1667) was a diplomatic devise that solidified a military, political and economic alliance between the Six Nations and representatives of the British Crown. It dictated that the two parties would meet frequently and “polish” the relationship between them so it would always shine and never tarnish. When British Royalty or Crown representatives came to visit the Six Nations, the Six Nations took the opportunity to remind the British of their alliance and anything that might be “tarnishing” it.

Between 1860 and 1919, there were 14 Royal/Vice Regal visits to Brantford and/or the Grand River Territory (http://brantford.library.on.ca/archive/index.php/archive/article/518). During many Royal visits, Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations would be decorated with evergreen archways and banners, blue, white, and red bunting and streamers, and Union Jacks. The Royal visitors would usually be met at the railway station or the city limits by large crowds waving small Union Jacks, while groups of children sang “God Save the Queen” to the accompaniment of a marching band. Local dignitaries would then address the visitors, after which a military guard would either escort the royals to a car which would tour or parade the visitors to the community’s significant sites. During the tour, the Royal visitors would dedicate buildings, monuments, or other sites. The Royal visitors would also stop at the H.R.M Royal Chapel of the Mohawks to sign the 1714 Queen Anne Bible before they headed to the Grand River Territory to meet with the Chiefs and enjoy more celebrations. Before the visitors would depart to their next destination, they would be presented with a gift to remind them of their visit to the area.

Two activities during these visits were unique to the Six Nations: the recounting of the long-standing British/Six Nations alliance, with continued expressions of ongoing loyalty, followed by any concerns or issues that might threaten the nature of their relationship, and the making of honorary Chiefs. Of the nine Royal visits for which members of Six Nations were present, at least three Royal visitors were made honorary Chiefs and there were at least five cases where Six Nations/British political issues were openly discussed. When the Six Nations and other First Nations people entered into a treaty relationship, they did so with the understanding that they were united in a family relationship.[4] By conferring honorary Chieftainships on Royal guests, this family relationship was maintained and strengthened. The enduring nature of the relationship was also underlined by the fact that treaty agreements never ended, even when one party violated their terms. Instead, the Six Nations and a representative of the British Crown would discuss the wrongdoing and amend it by making a new treaty.[5]

This family relationship can best be seen with Queen Victoria. Although she herself never came to Brantford, Brant County, or the Grand River Territory, her two sons did. Prince Albert (later King Edward VII) visited the area in 1860 and Prince Arthur (later the Duke of Connaught and Governor General of Canada) visited the area three times in 1869, 1913, and 1914. On Prince Arthur’s first visit, he was escorted to the Six Nations by the Burford Cavalry.[6] Once he met with the Chiefs, an honorary Chieftainship was conferred upon him. He later visited Brantford for lunch at the Commercial Hotel. During his second trip to the area, the now Duke of Connaught was met at the Brantford train station by a large crowd and inspected a troop of Boy Scouts before heading to the Six Nations territory, where he sat in  Council with his brother Chiefs.[7] Addressing the Duke during his third visit in 1914, Six Nations Chief A.G. Smith and Secretary Chief Josiah Hill reminded the Duke that the Crown needed to respect the treaty rights of the Six Nations as they had been ignored by the Canadian Federal government since the Department of Indian Affairs had been brought under the Canadian government’s control.[8] Smith and Hill further asked the Duke if he could secure a copy of the original treaty between the Six Nations and the British Crown to clarify whether the Six Nations were within their rights to demand such considerations from the Canadian government.[9] According to The Brantford Expositor, the Duke promised to consider this request.[10] In 1879, Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Louise and her husband, the Marquis of Lorne, also visited Brantford. After the usual reception at the Brantford train station, the Royal visitors opened the new Brantford Ladies’ College and the Lorne Bridge, which bears their name to this day. Although they did not have Chieftainships conferred on them or hear any political grievances, a Six Nations delegation was present during the dedication of the Lorne Bridge, further emphasizing the family connection between the Six Nations and Queen Victoria.

Council with his brother Chiefs.[7] Addressing the Duke during his third visit in 1914, Six Nations Chief A.G. Smith and Secretary Chief Josiah Hill reminded the Duke that the Crown needed to respect the treaty rights of the Six Nations as they had been ignored by the Canadian Federal government since the Department of Indian Affairs had been brought under the Canadian government’s control.[8] Smith and Hill further asked the Duke if he could secure a copy of the original treaty between the Six Nations and the British Crown to clarify whether the Six Nations were within their rights to demand such considerations from the Canadian government.[9] According to The Brantford Expositor, the Duke promised to consider this request.[10] In 1879, Queen Victoria’s daughter, Princess Louise and her husband, the Marquis of Lorne, also visited Brantford. After the usual reception at the Brantford train station, the Royal visitors opened the new Brantford Ladies’ College and the Lorne Bridge, which bears their name to this day. Although they did not have Chieftainships conferred on them or hear any political grievances, a Six Nations delegation was present during the dedication of the Lorne Bridge, further emphasizing the family connection between the Six Nations and Queen Victoria.

With Queen Victoria’s death in 1901, the people of Six Nations continued to value their family relationship with the British Crown, while Brantford and Brant County continued to support their ties to the British Empire, through her son, Prince Albert (King Edward VII). Although he would not return to the area after his visit in 1860, his son, the Duke of York (later King George V), came to Brantford in 1901 for a 20 minute visit. During this short trip, the Duke was welcomed at the Brantford train station by local dignitaries, the Dufferin Rifles, the Brantford Collegiate and Mohawk Institute cadets. In addition, he was presented a silver telephone by Prof. Melville Bell, commemorating the invention of the telephone in this area by his son Alexander Graham Bell.[11] Unable to make the trip to the Grand River Territory, the Six Nations conferred an Honorary Chieftainship on the Duke, then the Prince of Wales, in absentia in 1909. The Prince thanked the Six Nations for this honour, writing that he was “glad to learn that the Six Nations are as loyal to the British cause…as their forefathers”[12] and that “should the occasion arise for the British Crown to demand the similar services from the Six Nations in the future, they [the British] would not fail to maintain worthily the glorious traditions bequeathed them by their ancestors.”[13]

Representatives of the British Crown continued to make many trips to Brantford and the Grand River Territory leading up to the First World War. Although celebratory occasions for the people of Brantford and Brant County, the Six Nations, took this opportunity to not only proclaim their loyalty to the Six Nations/British alliance, but also to address any difficulties that had been “tarnishing” their alliance. During the Earl and Countess of Dufferin’s tour of Canada in 1874, after the Governor General turned the sod on the Brantford, Norfolk, and Port Burwell Railway and the Countess helped lay the cornerstone of the Young Ladies’ College,[14] the Earl of Dufferin made promises respecting Six Nations traditional treaty rights. Afterward Six Nations Chief Jacob General addressed the Earl of Dufferin, declaring that the Six Nations had the utmost confidence in their treaties made with the British. The Earl of Dufferin replied that “never shall the word of Britain once pledged be broken” and added that “every Indian subject shall be made to feel that he enjoys the rights of a freeman, and that he can with confidence appeal to the British Crown for protection.”[15] The Earl of Dufferin also stated that the Six Nations “must understand that it is no idle curiosity which brings me hither, but that when the Governor General and the representative of your Great Mother (Queen Victoria) comes among you it is a genuine sign of the interest which the Imperial Government and the Government of Canada take in your welfare.”[16]

This direct communication with Crown representatives was continued by the Six Nations when the Earls of Minto and Grey were appointed Governors General of Canada in 1898 and 1904 respectively. The Six Nations Council sent addresses reminding them of the Six Nations/British alliance, reminding the Governors General that the Six Nations fought to maintain the supremacy of Britain in Canada and because of this sacrifice, which cost the Six Nations their homeland in New York, the British Crown needed to protect the rights of the Six Nations from encroachments on their sovereignty.[17] The address to the Earl of Grey also promised that, if the British ever required it, the Six Nations would be “ready and willing to render faithful allegiance and support to the British Crown.”[18] Both Governors General would later visit Brantford and area in 1903 and 1905 respectively.[19]

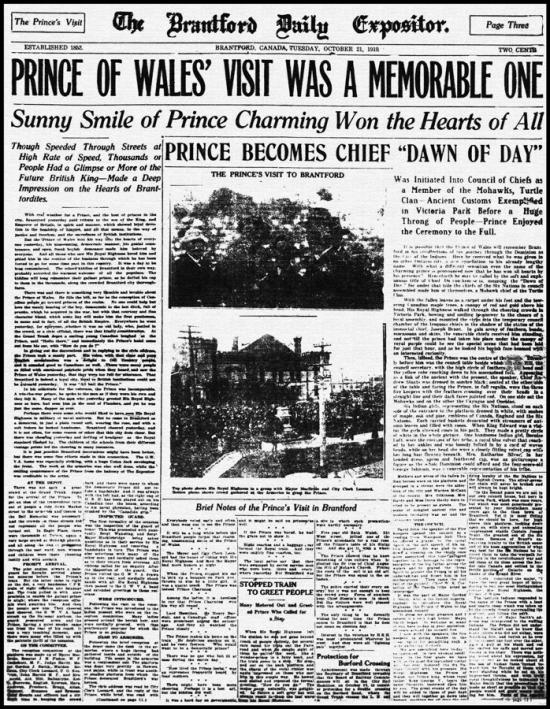

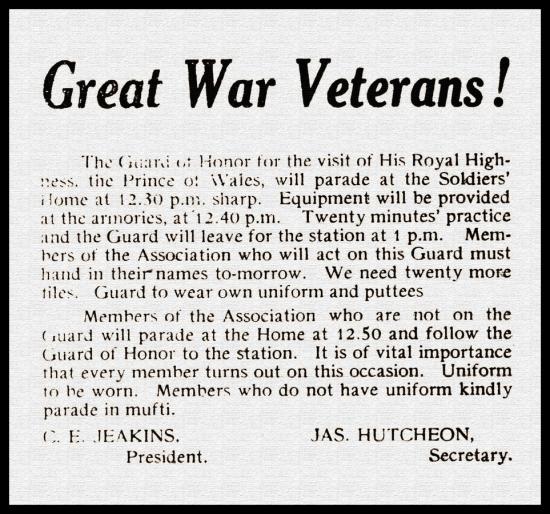

Although the First World War marked a change in the way Canada would interact with the British Empire, it did not diminish Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations’ royal connections. This can best be seen in the tour of the Prince of Wales in 1919. Excitement for his visit was so high that stories about the visit appeared in The Brantford Expositor three days before and continued two days after the Prince’s visit. For the most part, the usual ceremonies occurred. The Prince was met at the Brantford train station by crowds of people and local dignitaries while the Great War Veterans Association band played the national anthem.[20] Unlike previous Royal visits, the Prince’s honour guard on this occasion was not provided by the local militia, but by veterans of the Great War Veterans Association. After reviewing his honour guard, the Prince was driven to the armouries where he addressed the crowds. He maintained that, although his visit was to be a short one, he was delighted to make “acquaintance with the people of Brantford and of seeing some, at least, of the veterans from this district who fought in the Great War. I also wish to offer my sympathy to all those who have suffered dismemberment or loss.”[21]

Although the First World War marked a change in the way Canada would interact with the British Empire, it did not diminish Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations’ royal connections. This can best be seen in the tour of the Prince of Wales in 1919. Excitement for his visit was so high that stories about the visit appeared in The Brantford Expositor three days before and continued two days after the Prince’s visit. For the most part, the usual ceremonies occurred. The Prince was met at the Brantford train station by crowds of people and local dignitaries while the Great War Veterans Association band played the national anthem.[20] Unlike previous Royal visits, the Prince’s honour guard on this occasion was not provided by the local militia, but by veterans of the Great War Veterans Association. After reviewing his honour guard, the Prince was driven to the armouries where he addressed the crowds. He maintained that, although his visit was to be a short one, he was delighted to make “acquaintance with the people of Brantford and of seeing some, at least, of the veterans from this district who fought in the Great War. I also wish to offer my sympathy to all those who have suffered dismemberment or loss.”[21]

He then presented ten veterans from the area with various war medals, including a Military Medal to the mother of Pte. Ernest Baden Powell Davies, as Davies had been killed in action before he could receive his award from the Prince.[22] From the armouries, the Prince was taken to the Bell Memorial where he inspected veterans from the Army and Navy Veterans Association. After presenting the Prince with a book of historical notes, Miss. Augusta Gilkison was presented with a letter from the private secretary of Queen Mary thanking her for her patriotic work, especially with the I.O.D.E. and the Red Cross.[23] The Prince was then whisked off to the Mohawk Chapel to inspect the Mohawk Institute cadets, sign the Queen Anne Bible, and plant a fir tree given to him by Chief Augustus Hill; it was positioned close to the tomb of Joseph Brant.[24] Along the way the Prince passed by cheering groups of children from King Edward, King George, and Ryerson schools and saw the heavily decorated downtown of Brantford.[25] The front of the Returned Veterans Home on Dalhousie St., which was officially opened by the Duke of Devonshire in 1917 after the unveiling of the Bell Memorial, was decorated with bunting so the entire front of the building formed a Union Jack.[26]

After his visit to the Mohawk Chapel, the Prince was rushed to Victoria Park where he was to meet the Chiefs of Six Nations. Once on the stage erected in front of the monument to Joseph Brant, the Prince was introduced to the Six Nations Chiefs and the mothers and widows of the Six Nations soldiers who were killed in action during the War. The Chiefs then lead the Prince through the ceremony bestowing upon the Prince the Mohawk Chief’s title Da-yon-hem-seia (Dawn of Day) of the Turtle Clan.[27] After the ceremony, secretary of the Six Nations Confederacy Council of Chiefs, Asa R. Hill gave the Chiefs’ address. He stated that during the war:

“…the people of Six Nations have been your willing and loyal allies. The strong men of our nation eagerly enlisted in the army of the Dominion of Canada that we might serve the British Crown and the cause of world freedom…We have been steadfast for two and a half centuries, and your historians and officers have been pleased to record that it was the power of our arms that saved Canada for the British Empire when another nation contested for the Dominion. We have believed in British justice and have not been disappointed for the doctrine of the inherent rights of smaller nations is an ancient one with England. We are a diminishing power, yet for the time of our earliest contact, Great Britain has recognized our rights of sovereignty.”

Hill further stated that the Six Nations “rejoice in the friendship that Great Britain has bestowed upon us. We will defend the King and Empire with our lives. Call us and we shall be ready.”[28] Members of the Six Nations Patriotic League also conferred a Six Nations name to Queen Mary, giving her the name “the great, great woman, mother of love” (Ta-non-ronh-kiva).[29] After the naming ceremonies were over, the Prince unveiled and dedicated the Six Nations honour roll, which was struck on a bronze plaque. Further reaffirming the Six Nations connection to the British Crown, as the Prince left the stage to head to Princeton (where he spent the night), Catharine Silver, the oldest woman at Six Nations, presented him with a pin she had made by hand out of silver coins telling the Prince that “my great, great grandfather saved King George III from Washington. That is why we are British.”[30]

This reciprocal tradition of giving items made of silver as a representation their alliance continues today between the British Crown and the Hodinohso:ni. Although not on the Grand River Territory, Queen Elizabeth II gave the Mohawk people of the Bay of Quinte a set of eight inscribed silver bells to the Royal Chapel in Tyendinaga during her royal tour in 2010, further cementing the unique alliance relationship between the Hodinohso:ni and the British Crown. For the people of Brantford and Brant County, their tradition of celebrating their lineage as United Empire Loyalists has also continued with Queen Elizabeth’s tour of the area in 1997.

[1] The History of the County of Brant (Toronto: Warner, Beers, and Company, 1883), 341-343.

[2] F. Douglas Reville, History of the County of Brant (Brantford: The Hurley Printing Company, 1920), 240.

[3] Sally M. Weaver, “The Iroquois: The Grand River Reserve in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries, 1875-1945,” Aboriginal Ontario: Historical Perspectives on the First Nations, Donald B Smith and Edward S. Rogers eds. (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 1994), 220 and Brian Maracle, Back on the Rez: Finding the Way Home (Toronto: Penguin Books, 1997), 211-212.

[4] J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 8 and 10.

[5] Susan Marie Hill, “The Clay We Are Made Of: An Examination of the Haudenosaunee Land Tenure on the Grand River Territory” (Ph.D. diss., Trent University, 2006), 189.

[6] Reville, 201.

[7] Reville, 203 and 204 and The Brantford Expositor, February 15, 1913.

[8] Address by A.G. Smith and Josiah Hill to the Duke of Connaught found in RG10 , Vol. 3150, File 356,109 and The Brantford Expositor, May 9, 1914.

[9] Address by A.G. Smith and Josiah Hill to the Duke of Connaught found in RG10 , Vol. 3150, File 356,109.

[10] The Brantford Expositor, May 9, 1914.

[11] Reville, 197.

[12] Six Nations Council Minutes (May 4, 1909) found in RG10, Vol. 3007, File 218,222-133 and RG10, Vol. 3121, File 329,190.

[13] Six Nations Council Minutes (May 4, 1909) found in RG10, Vol. 3007, File 218,222-133 and RG10, Vol. 3121, File 329,190.

[14] William Leggo, History of the Administration of the Earl of Dufferin in Canada (Montreal: Lovell Printing and Publishing Company, 1878), 252-253 and Reville, 207.

[15] Jasper T. Gilkison, Narrative. Visit of the Governor-General and the Countess of Dufferin to the Six Nation Indians. August 25, 1874 2nd ed. (No Publisher, 1875), 12 and Leggo, 261.

[16] Leggo, 258 and Gilkison, 9.

[17] Letter from Six Nations Council to the Earl of Minto and the Earl of Grey (March 21, 1905) found in RG10, Vol. 2959, File 205,416.

[18] Letter from Six Nations Council to the Earl of Grey (March 21, 1905) found in RG10, Vol. 2959, File 205,416.

[19] Reville, 211.

[20] The Brantford Expositor, October 20, 1919 and Reville, 198.

[21] The Brantford Expositor, October 20, 1919 and Reville, 199.

[22] The Brantford Expositor, October 17, 1919 and Reville, 199.

[23] The Brantford Expositor, October 22, 1919 and Reville, 200.

[24] The Brantford Expositor, October 20, 1919 and Reville, 200.

[25] The Brantford Expositor, October 20, 1919.

[26] The Brantford Expositor, October 20, 1919 and Reville, 211.

[27] The Brantford Expositor, October 21, 1919 and Reville, 200.

[28] The Brantford Expositor, October 21, 1919.

[29] The Brantford Expositor, October 21, 1919 and Reville, 201.

[30] The Brantford Expositor, October 22, 1919.