Friend Or Foe?

Just as war enthusiasm was high, so too was suspicion directed at enemy aliens. Throughout the war years, various groups of people who had immigrated to Canada were discriminated against because of their difference.

One particular local incident, which can best be described as a kind of 'flag flap' highlights some of the tensions that arose in the days following the Declaration of War. The incident, as reported by The Brantford Expositor, concerned some young men who spotted, what they believed to be, a German flag flying at a Paris Road home. Outraged, they planned to confront the homeowner and tear down the offending flag. Fortunately, cooler heads prevailed and peace was maintained after it was pointed out to the boys that the flag in question was that of Holland.

Determining who was an ally and who was an enemy during the war was not an easy endeavor. The fate of local residents from the Ottoman Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy and other combatant and non-combatant nations illustrates this point. The 'friend or foe' confusion extended to the local Armenian and Turkish populations and it was left to a local Armenian missionary named Armen Amirkhanian to clarify matters.

Amirkhanian spoke to Brantford City Council and wrote a letter to the editor of The Brantford Expositor explaining that Armenians were not Turks and were loyal to Britain. He appealed to City Council to help those in the Armenian community who had suffered a higher than average unemployment rate following the outbreak of the war. In his letter to the editor, he reminded readers of the massacres of Armenian citizens at the hands of the Turks back in the years 1894 to 1896. His pleas had an impact because subsequent news reports spoke about the loyalty of the Armenians serving with the home guard and the suffering of the Armenian people more generally. Still, foreigners in Brantford were treated with suspicion and apprehension during the war.

Another example of the tension in town was the Dutch businessman Anthony S. Van Westrum - who was receiving what appeared to be an unusually large number of cables from Europe following the declaration of war. The Brantford Expositor pointed out:

A.S. Van Westrum of this city has been put to considerable annoyance since the war broke out, owing to people taking him for a German and calling him a "German Spy". He is not a German, but a Hollander, being on the reserve list of the army of the Netherlands and should a call be issued he would respond.[1]

Van Westrum was taken in for questioning by local police and the incident was duly reported in The Brantford Expositor on October 15 and 16. It was eventually revealed that several cablegrams had passed between him and his brother, L. S. Van Westrum. The brother was in Switzerland and was ill; Van Westrum’s wife was going to leave Brantford to be with him.

Yet, the cablegrams were addressed "Westrum, Brantford" and it is possible the authorities believed it was Anthony, not his brother's wife, who was set to leave for Switzerland. Anthony set the record straight by telling an Expositor reporter:

“I have no intention of leaving the city. I have business interests here, and I intend to remain. I am not a German as some people seem to think but a Hollander and my sympathies are all with the Allies in the present war.”[2]

Another group to receive a lot of attention during the war was the Turkish community. Within days of the Ottoman Empire declaring war, the local constabulary, on orders from federal officials, rounded up numerous members of Brantford's Turkish community. They were put on parole with orders not to engage in any activities that would hurt the war effort.[3]

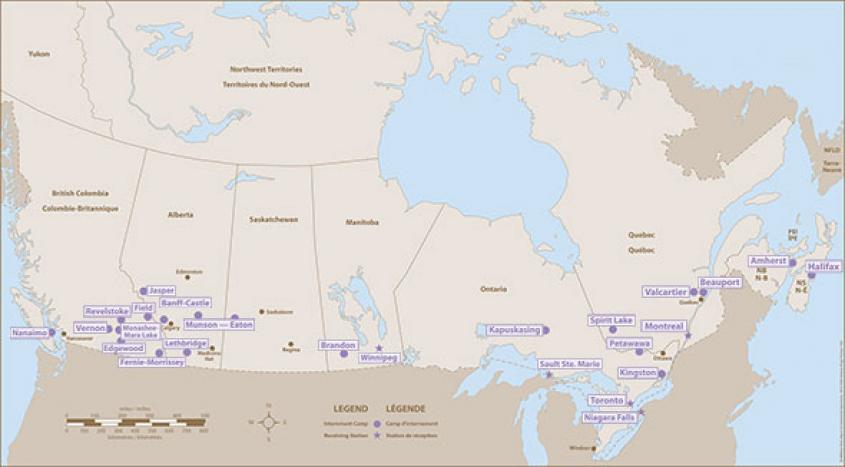

With the passage of the War Measures Act in August 1914, Turks, as well as Austrians, Germans and Armenians, could be required to register, take out residential certificates and, if deemed advisable by local authorities, placed in internment camps as Prisoners of War.

With the passage of the War Measures Act in August 1914, Turks, as well as Austrians, Germans and Armenians, could be required to register, take out residential certificates and, if deemed advisable by local authorities, placed in internment camps as Prisoners of War.

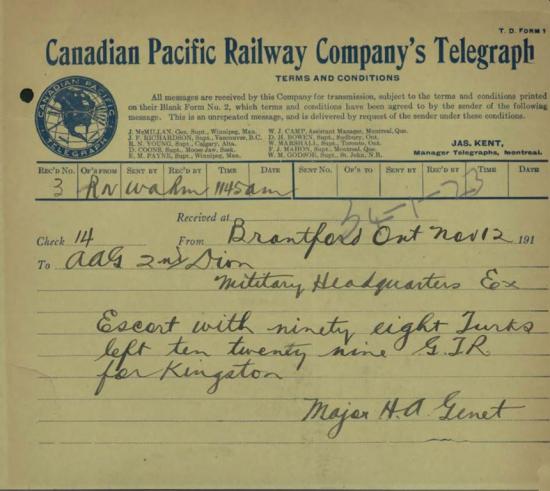

In Brantford, some 100 Turks were rounded up and on November 11, 1914. It was reported that they had been paraded from the county jail down Market Street to Dalhousie Street escorted by an armed guard. They remained at the armouries for a short time and then were sent to Kingston, again, under heavy guard provided by the 38th Dufferin Rifles. Meanwhile, the homes of people from Austria living in Brantford were searched by police looking for guns and ammunition. They found some weapons but it was reported the guns were to be used for a hunting trip that had been planned for out West.[4]

Overall, the impact of the war on these groups can only be described as devastating. In addition to living in difficult economic times, these groups lived under a cloud of suspicion. As of mid-October 1914 there were some 700 foreigners in Brantford who had become unemployed, including 350 who were thrown out of work in one fell swoop by a local factory.

There is considerable evidence that newcomers supported their new home and the war effort. By way of example, the Italian community contributed $112 to the Brant Patriotic and War Relief Fund and The Expositor published the names and addresses of those who donated money on Sept. 29, 1914. The names include Peter Cancella, of 270 Colborne St., Grancolo Vincenzo, of 35 Greenwich St. as well as Pietri Luciani, and Cavmino Latarri from Cainsville.

A couple of months later, The Expositor was reporting that local Italians who were reservists had received notification to report to the colors at once (Nov. 26, 1914) and on Dec. 11 1914, The Expositor reported that two more Italian reservists had left for their mother country, making a total of six that had left Brantford that week.

WWI Internment Camps Across Canada