The Cadet Movement

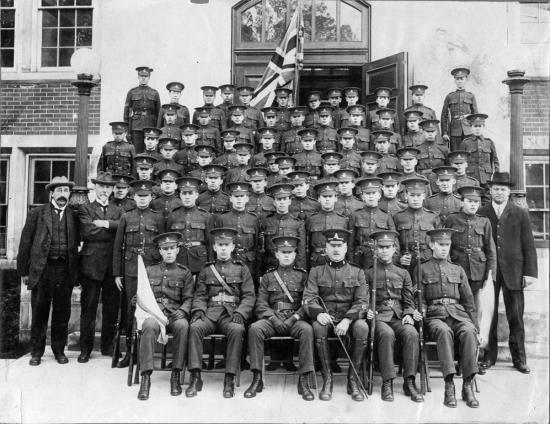

When the cadet movement came to Brantford, Brant County and Six Nations in the 1890s, many people saw it as a universal system of military training that could instill proper British values into the area’s youth and encourage their enlistment in the Canadian militia system. By 1914, Brantford and Six Nations would have at least seven active cadet corps, leading to high enlistment rates during the war for both communities.

Although officially launched in the late 1890s, cadet corps, drill associations, and other youth military training initiatives began in the Brantford, Brant County and Six Nations area as early as the 1870s. Usually sponsored by schools or religious groups, cadets corps were either part of a school’s physical education program or an after school activity, saving children from the growing industrial streetscape of Brantford.

The area’s first official cadet corps was formed at the Brantford Collegiate Institute (BCI) in 1898, but the Brantford Expositor reported that, even before the corps was created, the students of BCI were already drilling with decommissioned rifles under the direction of members of the 38th Dufferin Rifles.[1] This group, officially named No. 46 Cadet Corps, immediately connected with Brantford’s growing sense of militarism and concern over the defense of Canada. Many people hoped that the military training BCI students received in the school would lead to their participation in the Canadian military.[2]

Although their uniform styles would change leading up to the First World War, the BCI cadets’ first uniform consisted of a dark blue serge tunic with black and white trim and trousers of the same blue with a scarlet pipe down the outside seam.[3] This uniform was bought and paid for by the cadets through sold-out public concerts and private donations.[4] Participating in inspections, summer camps, church parades, competition marches, and mock battles,[5] the BCI cadet corps became the premier corps in the City. The wife of the mayor of Brantford personally hand-stitched and presented the cadets with their colours in May 1898.[6] They were also used as the honour guard for sending and receiving Brantford’s troops to and from the Anglo-Boer War and for the Duke of York, the Earl of Minto, and the Lt. Governors Sir Mortimer Clark and Sir J.H. Gibson when they visited Brantford.[7] By 1911, after the All-Canada Marksmen Competition, three BCI cadets were chosen to be part of the Canadian Cadet Rifle Team at the Bisley Cadet Rifle Competition in England.[8] The BCI cadets became so popular that the program was expanded in 1913 into the public school system with seven new cadet companies located in various elementary schools throughout the city.

The cadet corps trend was mirrored in other areas around the city. The beginning of the Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps is difficult to pinpoint. Established in 1834, the Mohawk Institute did not take a militaristic turn until 1870s, under administration of Rev. Robert Ashton. Although not an official cadet corps, Ashton ran the school in a military fashion. Six Nations students were required to form up on the parade square, number themselves off, and break into squads with sergeants and corporals before beginning their daily chores.[9] Ashton also created good conduct badges and black lists, and taught the students “lining up and marching to the dining-room, the classroom, the chapel, etc.”[10] By 1894, Ashton had the boys of the school wearing polished boots and grey uniforms tailored by the girls of the institute.[11] After teaching the students drill, Ashton would put on military displays for visiting officials and the Brantford public.[12] A brass band was added to these shows in 1899.[13] When Rev. Robert Ashton retired in 1903, his son A. Nelles Ashton took over the operation of the school and officially established No. 161 Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps in 1909.

Although Rev. Robert Ashton started the military structure of the school as a means of controlling and changing the behavior of the Six Nations students, by 1910, the Department of Indian Affairs recommended drill and callisthenic exercises be used as physical education in Canada’s Residential School system. The Department of Indian Affairs produced its own 23-page manual with many breathing exercises “as Indian children show a tendency towards pulmonary diseases.”[14] These exercises were to be used to foster good health among the students, but also to assimilate them into Euro-Canadian society by teaching children the “proper” non-Native ways of moving their bodies in a unified and orderly manner.[15]

Although imposed on Six Nations children to train them to be more like Euro-Canadians, some children used the cadet corps as a way of surviving the residential school experience. Through cadets, students were allowed to travel off school grounds and were able to compete, and sometimes win, against non-Native cadet corps, creating pride among the students. During their 1908 inspection, the reviewing officer claimed that the Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps made a “very credible showing.”[16] By 1912, The Brantford Expositor reported that the corps was “awarded the place of honor by the inspector over the cadet corps of Toronto, Hamilton and practically central Ontario.”[17] Only a year after being outfitted with Ross Rifles, the Mohawk Institute Cadets won first place in the No. 2 Central Ontario Military District rifle competition in 1912.[18] Due to their award winning drill and presentation, the Mohawk Institute Cadets often made public appearances in Brantford and were presented to British royalty during their visits to the area.[19]

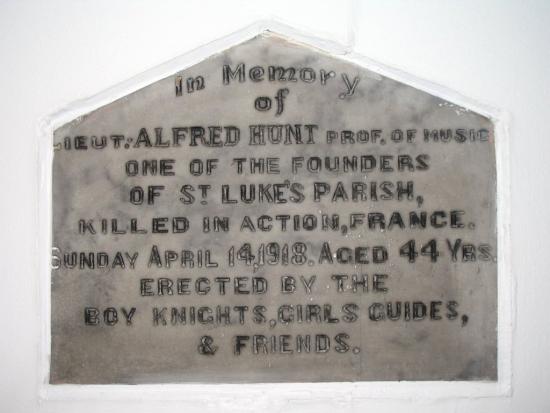

In an effort to save Brantford’s youth from the debilitating effects of its industrial growth, Prof. Alfred Hunt formed the St. Luke’s Boy Knights cadet corps in 1900 after meeting with the leader’s and youth of St. Luke the Evangelist Anglican Church.[20] With the motto “Upbuilding of Boys Physically, Morally and Spiritually,”[21] Hunt began a co-ed youth group that not only had its own cadet corps for boys, but also held Bible classes,[22] and a well-attended summer camp complete with a supervised playground.[23] For young girls, classes in painting and sewing were also offered.[24] By 1916, Hunt had at least 30 girls taking part in his youth group.[25] Although never fully autonomous from St. Luke’s, Hunt and the Boy Knights established their own armouries on Murray Street, where their cadet and other programs were offered.[26]

For its first ten years, the Boy Knights were completely supported and funded by the people of Brantford and St. Luke’s through popular public concerts, drills, and recitations.[27] On May 12, 1911, the Brantford Boy Knights were officially gazetted as Cadet Corps No. 302, enabling the corps to take part in national and international cadet competitions. In 1914, the Boy Knights came in fourth place in the Imperial Shield Challenge. In 1915, they improved their standing to second place out of an entry pool of 700 different corps from across the British Empire.[28] By 1914 the group claimed to have 100 children enrolled in its various programs.[29]

The Methodist church in Brantford, following the lead of other Methodist churches across Ontario, did not support the cadet movement due to its overt military overtones; instead, the Methodists supported the Boy Scouts. Between 1910 and 1914, four Boy Scout troops were active in Brantford, including the Brant Avenue Methodist Troop, the Colborne Street Methodist Troop, and the Wesley Methodist Troop, with the lone Anglican troop being run out of Trinity Church in Eagle Place.[30] In October 1911, The Brantford Expositor reported that there were at least 125 Boy Scouts present in the City of Brantford.[31]

With the coming of the First World War, cadet corps in Brantford grew. Anglican churches in Brantford formed their own corps in December 1914, with two companies being formed at Grace Anglican Church, one at St. Paul’s Church in Holmedale, and another forming at Holy Trinity in Eagle Place.[32] Among existing cadet corps, numbers also rose. The Brantford Public School Cadet Battalion gained a new company in December 1915, while St. Luke’s Boy Knights’ official roll jumped from 120 to 200 Boy Knights.[33]

The War saw many ex-cadets enlist into the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The Knights reported that no less than nine ex-Boy Knights enlisted with the first contingent,[34] and by 1916, the Boy Knights claimed that 45 former members had enlisted since war was declared.[35] In March 1916, Prof. Hunt even tried to raise a platoon of Boy Knights for the 215th Battalion.[36] Although this plan was not acted upon, Prof. Hunt himself would enlist in the 111th Battalion out of Galt, Ontario[37] and was killed in action on April 14, 1918.[38]

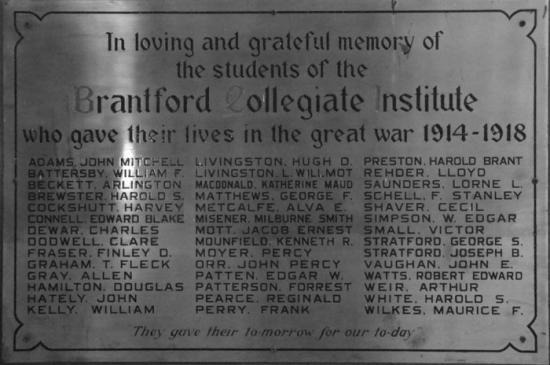

Even though over 500 boys had passed thought the BCI Cadet Corps by 1913, [39] and many of its ex-members had later joined the Canadian military,[40] it is hard to say how many of these ex-cadets enlisted in the First World War. F. Douglas Reville would subsequently state that a large percentage of officers that left Brantford for overseas service had come from the ranks of the BCI cadet corps,[41] with the BCI Honour Roll, listing 41 men Killed in Action. These remain the lone testament to the role of the BCI Cadet Corps in the Great War.

As with the BCI Cadets, many ex-cadets from the Mohawk Institute continued their military service in the 37th Haldimand Rifles. Mohawk Institutes’ Honour Roll at the Mohawk Chapel lists 83 ex-students who enlisted in the First World War, with six staff and students making the supreme sacrifice. [42]

Although the Boy Scouts of Brantford were also affected by the war, it is unknown if their numbers grew as Brantford’s cadet corps had grown. Many Boy Scout leaders enlisted in the Canadian military, leaving some troops leaderless. Some Boy Scouts would enlist with almost the entire Senior Patrol at Holy Trinity enlisting after a rather patriotic and rousing sermon by Rev. McKegney.[43]

By 1916, the anti-war movement began creeping into the Brantford area with many questioning the school board’s support of the cadet program.[44] Although many groups came to the defense of the corps, including veterans’ organizations, the Brantford Patriotic League, and the Dufferin Rifles,[45] in February 1919, the school board announced that it would abolish the cadet program within their schools.[46] The final inspections of the BCI and Public School Cadet Corps took place in May 1919.[47] Soon afterward, however, the BCI Cadet Corps would be revived, surviving until 1972.

After the disbanding of BCI and Public School Cadets, other corps followed suit. Although popular before the war, St. Luke’s Boy Knights disbanded in December 1919. Holy Trinity disbanded their cadet corps in July 1920 and the Grace Anglican Church Lads Brigade disbanded in April 1922. All three Anglican cadet crops were never revived again.

The Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps was officially disbanded in 1925, but the militaristic organization of the school continued. Six Nations children were still taught to line up and march, break off into squads or work details, and wear school uniforms, which were made out of surplus material purchased from military authorities.[48] The Mohawk Institute Cadet Corps was revived in 1949 under Rev. Canon W.J. Zimmerman.[49]

Even the Boy Scouts were not immune to the anti-war movement, with all corps being suspended until 1921. Although 1200 boys registered city wide for the reconstituted Boy Scouts in 1921, there were not enough leaders as many had been killed or wounded during the war.[50]

[1] The Brantford Expositor, March 21, 1898 and October 25, 1898.

[2] The Brantford Expositor, March 23, 1889.

[3] The Brantford Expositor, March 29 and April 12, 1898.

[4] The Brantford Expositor, April 6 and December 7, 1898.

[5] The Brantford Expositor, April 6, 1898, May 28, 1898, May 30 1898, June 13, 1898, December 7, 1898, May 28,1900, May 30, 1900, January 4, 1913, May 20, 1913, July 8, 1913, July 11, 1913, May 8, 1917 and May 23, 1919.

[6] The Brantford Expositor, January 4, 1913.

[7] The Brantford Expositor, May 4, 1912

[8] The Brantford Expositor, April 25, 1911. This was nationally impressive as BCI was able to provide three cadets out of a team made up of one cadet from Toronto, two cadets from Hamilton, and six cadets from various communities in Quebec.

[9] Elizabeth, Graham, The Mush Hole: Life at Two Indian Residential Schools (Waterloo, Ontario: Heffle Publishing, 1997), 91.

[10] Graham, 9, 23, 40 and 90.

[11] Graham, 93 and 96.

[12] Graham, 93 and 96.

[13] Graham, 97.

[14] Government of Canada (Department of Indian Affairs). Calisthenics and Games Prescribed for use in all Indian Schools. Pamphlet, 1910, 3.

[15] Anne Bloomfield, “Drill and Dance as Symbols of Imperialism,” in Making Imperial Mentalities: Socialization and British Imperialism, J.A. Mangan ed. (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1990), 74-93.

[16] Graham, 105.

[17] The Brantford Expositor, January 6, 1912.

[18] Graham, 106.

[19] F. Douglas Reville, History of the County of Brant Vol. 1 (Brantford: Hurley Printing Company, 1920), 197, 200, and 201.

[20] From “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[21] From “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[22] The Brantford Courier, July 18, 1914.

[23]The Brantford Courier, July 18, 1914.

[24] The Brantford Courier, July18, 1914.

[25] “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[26] “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[27] The Brantford Courier, December 31, 1913.

[28] “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives. Although placing second in the British Empire, the group placed first in the all Canadian Shied Challenge.

[29] The Brantford Courier, July 18, 1914.

[30] The History of Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Eagle Place, Brantford, Ontario, 1903-1967 (Brantford: Holy Trinity Church, 1967), 39 and The Trinity Times, (Brantford: Holy Trinity Church, 1967), 2012.

[31] The Brantford Expositor, October 23, 1911.

[32] The Brantford Expositor, December 16, 1914.

[33] The Brantford Courier, July 18, 1914 and “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[34] The Brantford Courier, November 7, 1914.

[35] “The Visit of the Australian Cadets to Brantford 4 and 5 Jan. 1916”, Brant Museum and Archives.

[36] The Brantford Expositor, March 7, 1916.

[37] The Brantford Courier, May 23, 1916.

[38] Douglas F. Reville, History of the County of Brant Vol. 2 (Brantford: The Hurley Printing Company, 1920), 510.

[39] The Brantford Expositor, January 4, 1913.

[40] The Brantford Expositor, May 4, 1912 and May 2, 1912.

[41] Reville, History of the County of Brant Vol. 2, 440.

[42] Mohawk Institute Honour Roll. St. Paul’s Her Majesty’s Royal Chapel of the Mohawks.

[43] The History of Holy Trinity Anglican Church, Eagle Place, Brantford, Ontario, 1903-1967, 39.

[44] The Brantford Expositor, May 4, 1917.

[45] The Brantford Expositor, February 28, 1919, February 15, 1919, March 8, 1919, February 7, 1919, and May 10, 1917.

[46] The Brantford Expositor, February 7, 1919.

[47] The Brantford Expositor, May 23, 1919.

[48] Graham, 120 and 121.

[49] Graham, 28.

[50] The Brantford Expositor, December 20, 1924.