Battles Of The First World War

One of the most interesting phenomena of the Great War was the way in which Empires were mobilized. Colonial people from around the globe found themselves plunged into a conflict half a world away, often with little idea why they were fighting. The British Empire was instrumental in the War, with troops from India, South Africa, the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand and Canada all playing their part.

For this country, the First World War marked an important stage in the emergence of Canada as a self-aware nation. While it is not quite so simple as saying that Canada gained independence as a result of the War, it is true that the conflict contributed a great deal to the rise of Canadian nationalism. This reality is all the more complex when we consider that, for members of Six Nations, there was frequently no desire to promote Canadian nationalism.

Second Ypres

Yes, we held intact. The 8th Battalion was on the apex of the attack. There was only two in my platoon that done it. There was a chap by the name of Bill Cox and myself. Well, I knew that due to the fact that I'd served my apprenticeship as a plumber and had put it on previously, you know, in civil life whenever gas got strong. Now, whether there's any neutralizing effect in the urine, I couldn't tell you but we were run out of water. You see, they weren't able to get supplies up and you weren't very fussy on what you done…[1]

As the two sides in the Great War began to realize that this was not going to be, as imagined, a war of movement, the front began to solidify. On the Western front, this resulted in a line of trenches that extended from the Channel all the way to the Swiss border, covering some 700 kms.

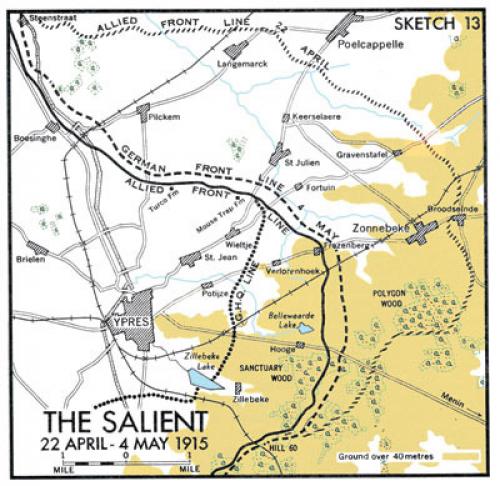

In a war like this, any position that jutted out into enemy territory was a serious liability. This was the case with the Ypres salient, a sector that bulged into German held land and which, consequently, became hotly contested.[2]

The Second Battle of Ypres (there had already been a previous engagement in October and November 1914[3]) began on April 22, 1915. It is significant in Canadian memory for several reasons. It was the first major battle in which elements of the Canadian Expeditionary Force participated. In addition, it was the scene of the introduction of a new weapon: chlorine gas. Though the Allies were also experimenting with this type of weapon, they reacted strongly to the Germans’ use of gas.[4]

The first gas attack occurred around 5 p.m. on April 22 and was focused on trenches occupied by the French. The yellow-green cloud that crept towards their positions was first thought to be a simple diversion but quickly the horrible truth became clear.

French soldiers braced themselves for an attack but were soon unable to function amidst the choking cloud. They began to cough violently and started suffocating after inhaling the chlorine gas. Many of them died, drowning as their lungs filled with liquid. As panic set in, they began to abandon their positions leaving a huge gap in the Allied line and exposing the Canadians next to them. The Canadian troops, however, held the line, shifting their position to cover the gap that had been created. They were aided by the fact that the Germans, unsure of this new weapon themselves, did not fully exploit the advantage they momentarily held.

On April 24, the Germans launched another chlorine gas attack, this time aimed directly at the Canadians. Instead of fleeing, the Canadians counterattacked and then fell back, inflicting significant casualties on the Germans.[5] This permitted the Allies time to bring up additional troops to ensure that Ypres did not fall into German hands. Strategically, it was important that the Canadians halted the German advance and held Ypres. It prevented the Germans from forcing their way into France from the north and enabled the allies to protect French ports located on the English Channel.

The cost was high, however. The battle claimed more than 6,000 Canadian casualties. Locally, it took a significant toll, in the form of Cameron D. Brant, great-great grandson (on both his maternal and paternal sides) of Joseph Thayendanegea Brant. A measure of the respect in which the family was held by local non-Aboriginal leaders was provided in the letter of condolence that was sent to Brant’s family in the wake of news of his death. This news reinforced the fact that all families in the region, regardless of their notoriety, were making sacrifices in this conflict.

Arguably the most significant impact of this battle was that it helped forge a strong reputation for Canadian forces. Even before the bloodiest of the battles in 1916 and beyond, the Canadians were beginning to earn praise for their resilience and courage. The pride that was also building is evident in the description of the battle provided by one chronicler of the encounter:

The defence put up by the Canadians was, as might be expected, stern. The line could not be more than thinly manned but the Canadians fought hard and sold each scrap of land and each casualty dearly to the advancing Germans. In one instance, two platoons of the 13th Battalion were completely wiped out by a superior force of Germans which was, however, held up thanks to the sacrifice of the Canadian platoons. It is to the 13th Battalion that the distinction goes for the award of the first Victoria Cross for the Second Battle of Ypres. This award was made, posthumously, to Lance Corporal Frederick Fisher, who used his machine gun to great effect in front of the grave-yard in Saint Julien, and so helped to prevent the Germans pressing on to that village.[6]

The honours won by Canadians, and the reputation built for ingenuity, endurance and bravery would only grow as a result of future battles.

Battle of the Somme

Battalions attacked in four or eight waves, not more than 100 yards apart, the men in each almost shoulder to shoulder, in a symmetrical well-dressed alignment and taught to advance steadily upright at a slow walk….[E]ach man carried about 66 lbs, over half his own body weight, which made it difficult to get out of a trench, impossible to move quicker than a slow walk or to rise and lie down quickly…even an army mule, the proverbial natural beast of burden, is only expected to carry a third of his own weight.[7]

If there is one battle that shaped the image of courageous men being led by inept generals – the infamous “Lions led by Donkeys” interpretation of the Great War – it was the Battle of the Somme, launched on July 1, 1916.[8]

The Somme is an important battle for many reasons, chief among them the incredibly high number of casualties suffered by British and Empire troops. On the first day of the attack alone, the British Army suffered more than 57,000 casualties, all for a mere 3 square miles of gained territory. This was the single most costly day in the history of British warfare. It is perhaps not surprising that, given this steep cost, an analysis of the battle focusing on outmoded tactics and callous leaders developed. Nevertheless, while there is no denying that the battle was extremely bloody, the popular image of the Somme, cemented by the likes of Basil Liddell-Hart in passages like the one above, is over-simplified. As one recent work on the Somme has argued, the image of men serenely advancing in tight formation as they were scythed down by the Germans is inaccurate.[9]

Whatever the reasons for the attack’s ultimate failure, the casualty figures are staggering. Still, the eagle’s eye view does not always do justice to the carnage. Sometimes a narrower focus hits home more effectively. This is illustrated by the fate of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment, which fought on July 1.[10] Back then, Newfoundland was not part of Canada and so its soldiers fought separately, under the British. The Newfoundland Regiment suffered what can only be termed horrific casualties on the first day of the battle.

Near the tiny village of Beaumont Hamel, the Newfoundland Regiment moved into the firing line on Easter Eve, April 22. Some 300 to 500 metres distant, down a grassy slope, lay the German front lines. These German positions were occupied by the men of the German 119th Reserve Regiment, tough and experienced; they had turned the natural defences of a deep Y-shaped ravine into one of the strongest positions on the entire Somme front.

At 9:00 p.m. on June 30, the regiment turned out for the final time: 25 officers, 776 NCOs and other ranks. Among the young men preparing for their first experience of going over the top there was little evidence of foreboding. “It is surprising to see how happy and light-hearted everyone is,” Lieutenant Owen Steele noted in his diary. He added: “The climax of our troubles will be reached within the next few days after which the day of peace will quickly draw near.”[11] He was dead six days later.

The July 1 attack of British forces (intended to relieve pressure on the French, who were locked in a battle to the death at Verdun) was launched as planned. Immediately, the opening phase of the attack faltered under withering enemy fire. Confusion was exacerbated by poor communication. General de Lisle mistook German flares for a signal of early success and therefore ordered the 88th Brigade made up of the Essex and Newfoundland Regiments to attack “as soon as possible.” But the Essex soldiers were unable to leave their trenches because of the large number of dead and wounded

As a result, the Newfoundlanders moved off alone at 9:15 a.m., their objective the first and second line of enemy trenches, some 650 to 900 metres away. They moved down the exposed slope towards No Man’s Land, the rear sections waiting until those forward reached the required 40-metre distance ahead. No friendly artillery fire covered the advance.

A terrible cross-fire tore into advancing columns and men began to drop, especially as they approached the first gaps in their own wire. Doggedly, the survivors continued on towards enemy. “The only visible sign that the men knew they were under this terrific fire,” wrote one observer, “was that they all instinctively tucked their chins into an advanced shoulder as they had so often done when fighting their way home against a blizzard in some little outport in far off Newfoundland.”[12]

The few men who did manage to attain the objective of the German lines were confronted with a chilling discovery: the artillery barrage prior to the attack had not cut the German barbed wire. The night before, a report by a Newfoundland reconnaissance team had alerted commanders to this fact but they had been ignored.

On the night of July 1, the search began for survivors. When the roll call was taken, only 68 men responded. The full cost would not be known for several days. The final figures revealed that the regiment had been virtually wiped out: 710 killed, wounded or missing. Most were struck down before they reached beyond their own front line.[13]

Vimy Ridge

“It was a grand sight to see the guns behind us. We looked back and saw the spurts of guns for miles and heard the crack of machine guns. Now in front we saw the dirt fly, it looked as if the earth was lifting. You get to the fellow next to you and shout as loud as you can and he can hardly year you. I would give anything to see another sight like that. If the guns could have kept up that day I believe we could have run the Germans to Berlin

Well mother, I will close for this time, with love, from your loving son, Arthur."

P.S. My wounds are pretty sore.”[14]

These are the words of Arthur Daiken, who described the Canadian attack on Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917. They are typical of soldiers in the Great War, only hinting at the horror of battle and focusing more on the resolve of the men at the front to “run the Germans to Berlin.”

Daiken, of Brantford, was wounded but survived this most famous of Canadian battles. His brother Arden was not so fortunate. He was one of the 10,500 casualties including almost 3,600 dead in this important battle.[15] Part of the reason that Vimy was significant was that, under the leadership of Lt.-Gen. Sir Julian Byng and Major General Arthur Currie, all four Canadian Corps fought together for the first time in the Great War. It was also a significant encounter because it reinforced the reputation of Canadian troops, who succeeded in taking an objective that earlier assaults by both the British and French had failed to win.

This construction – victory where the British and French had previously failed – has been used frequently by those writing about Vimy Ridge. Perhaps nowhere was it more powerfully invoked than in the writing of Pierre Berton. In his Vimy, Berton related the following story:

Everybody liked the anecdote told by a young gunnery officer from the 25th Battery who, returning from England on Easter Monday, got the news in a cafe at Houdain that the Ridge had been taken. A group of French officers at a nearby table who heard shook their heads. “C’est impossible,” one declared. Then he was told that the Canadians had done the job. “Ah! Les canadiens!” he responded. “C’est possible”[16]

But, as with the myth of “Lions led by Donkeys”, the “Canadians succeed where British and French fail” hypothesis obscures a more complex reality.

Recent scholarship has explored the complexity of the situation to great effect.[17] It has emerged that, on the one hand, the lessons learned by both the British and French in debacles like the Battle of the Somme helped the Canadians to succeed in 1917. In addition, without valuable contributions from both their Allies, in terms of tactical innovations, artillery support and leadership, the victory at Vimy would not have been possible.

Put simply, Vimy Ridge cannot simply be ascribed to the superior moral fibre of Canadian troops. There were a number of important interconnected factors that led to Canadian success. Some of the most important factors were:

Preparation: Gen. Currie had faith in the men under his command. He believed that it was important to provide them with as much information as possible and he also was convinced of the power of rehearsal in overcoming the confusion of the attack. Currie insisted that soldiers be provided with maps of the ground they were to cover prior to the assault. This would assist them to reorient themselves in the event that they were separated from their units. Currie also demanded that his men practice continually. The Canadians spent hours prior to the Easter assault practicing their movements, often on taped out models of the battlefield. Again, the aim was to help overcome the potentially devastating impact of battlefield confusion;

Preparation: Gen. Currie had faith in the men under his command. He believed that it was important to provide them with as much information as possible and he also was convinced of the power of rehearsal in overcoming the confusion of the attack. Currie insisted that soldiers be provided with maps of the ground they were to cover prior to the assault. This would assist them to reorient themselves in the event that they were separated from their units. Currie also demanded that his men practice continually. The Canadians spent hours prior to the Easter assault practicing their movements, often on taped out models of the battlefield. Again, the aim was to help overcome the potentially devastating impact of battlefield confusion;- Artillery: it is critical to understand that the victory at Vimy was not an entirely Canadian affair, though even some in other countries have accepted this inaccurate portrait.[18] World War I was, in many respects a gunner’s war and it was no different at Vimy. Any account of Vimy Ridge must acknowledge that the artillery that so ably assisted the infantry was largely British. The artillery was successful in two main respects. First, it was realized from an early stage that counter-battery efforts needed to be a primary focus. Techniques developed by Canadian general, Andrew McNaughton, helped knock out German guns very quickly, thereby enhancing the Canadian infantry’s ability to move. Secondly, the “creeping barrage”, by which shelling moved forward at a pre-arranged pace just in front of the leading edge of the infantry, allowed men to march at a steady pace, while clearing an unobstructed path to the main objective;

- Initiative: Currie had been impressed by recent French innovations which provided a higher degree of initiative to junior officers. He embraced a degree of decentralization that allowed officers closer to the actual fighting to react to conditions on the ground as expeditiously as possible.

The above list is by no means complete. However, even this partial list of advantages makes it clear that the Canadians who attacked Vimy Ridge were well-trained and well-prepared, and had been properly informed about the overall battle strategy before the attack.

Passchendaele

Surrounded by the roar of exploding shells and the incessant popping of gun fire, David Sinclair Van Fleet trudged through knee-deep mud towards a first aid station. Van Fleet, who had worked for Massey-Harris prior to enlisting, and a comrade were swallowed up by the muddy Passchendaele battlefield on November 6, 1917. [19]

Van Fleet and his friend were among the 15,654 Canadian casualties at Passchendaele, also known as the Third Battle of Ypres. It was bloody and it was muddy. For those convinced that Haig was an incompetent butcher, the prime piece of evidence is Passchendaele. However, once again, the reality of the situation was more complicated than some would have us believe. The Germans return to unrestricted submarine warfare convinced many senior Allied leaders that a major offensive was necessary. Haig had been convinced for some time that a push in the Ypres salient was what was required and he even discussed this with the French in May 1917. It was only in the subsequent months – when the scale of the mutinies in the French Army became apparent – that plans were altered to spare French forces.

This might have given planners pause. However, recent events in the region of Ypres had given rise to renewed optimism. On June 7 the Second Army had launched an assault on Messines Ridge, in the course of which nineteen massive mines were exploded. Those defenders who survived were rendered ineffective and the attack was deemed a great success.[20]

Prime Minister Lloyd-George was less optimistic than his military advisors. He believed that, with Russia withdrawing, France uncertain, and the United States not yet fully engaged, it was best to be prudent. However, Haig was convinced that, given their allies’ weak position, it was all the more important that the British strike. Eventually, Haig won the debate. The consequences would be heavy indeed.

On July 31, 1917, at 3:50 a.m., the attack was launched. A fifteen day bombardment with some four million shells preceded the offensive. The initially promising pace was slowed by communication problems and by rains, which, by the first week of August, had left the battlefield a churned up mess. It was not uncommon for the terrain to be compared to porridge.[21]

On September 4, Haig was called to London to explain the situation. He had already switched the 5th Army for the 2nd, giving Sir Herbert Plumer, long active in the Ypres sector and beloved due to his concern for his troops, charge of the attack. Plumer proposed a less ambitious plan, emphasizing what became known as “bite and hold” tactics. Shorter range objectives would be the focus and an appropriate pause would be worked in prior to each successive assault.[22]

This is where Canadian troops became involved. The Passchendaele meat grinder had severely depleted British strength. Haig turned to the ANZACs and Canadians. Despite strong misgivings, Sir Arthur Currie eventually complied with his orders and sent the Canadians in. October 26 marked the first day of the Second Battle of Passchendaele, Canadian troops broke what the Germans termed the First Flanders Position. After a brief rest the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions secured the rest of Passchendaele village on November 6. Four days later, the line was consolidated.

While Currie was justifiably proud of his men he also felt vindicated. The success of the Canadians had come with a huge price tag, with 15,634 killed or wounded. This was almost precisely the figure that Currie had predicted when first approached about an offensive.[23]

Hill 70

It may not be as firmly etched in the minds of Canadians as the battle of Vimy Ridge, but for the people of the Six Nations, Brantford and Brant County, the Battle of Hill 70 is of great significance. The assault on Hill 70 was intended to act as a relief effort for the British forces in the Passchendaele sector, and many men from the Canadian Corps, including men from Six Nations, Brantford, and Brant County were added to the Canadian casualty lists. Of the 300 Six Nations men who enlisted, five men were killed while another seven were wounded in this action. In addition to these Six Nations loses, 10 casualties from Brantford and Brant County were also reported killed or wounded during the campaign.

In order to draw fire away from the Passchendaele sector, the British high command instructed the Canadian Corps to capture the French mining town of Lens. Canadian General Arthur Currie protested as he felt that Lens, in a valley between two hills, would lead to high casualties. Currie proposed that the Canadian Corps should attack Hill 70, just outside the town, forcing German troops to counterattack against a strong defensive position.[24] As with his plan at Vimy Ridge, Currie pulled the Canadian Corps from front line duty for extensive training. For the month of July, the Corps prepared through mock battles, map memorization, and classroom training.[25] On August 1, 1917, the Corps was moved back into the frontlines to await orders.[26]

In order to draw fire away from the Passchendaele sector, the British high command instructed the Canadian Corps to capture the French mining town of Lens. Canadian General Arthur Currie protested as he felt that Lens, in a valley between two hills, would lead to high casualties. Currie proposed that the Canadian Corps should attack Hill 70, just outside the town, forcing German troops to counterattack against a strong defensive position.[24] As with his plan at Vimy Ridge, Currie pulled the Canadian Corps from front line duty for extensive training. For the month of July, the Corps prepared through mock battles, map memorization, and classroom training.[25] On August 1, 1917, the Corps was moved back into the frontlines to await orders.[26]

To weaken German defenses, Currie ordered his artillery to shell the German troops on the hill with both regular and gas filled shells.[27] In retaliation, the Germans also shelled the Canadians with regular and gas shells for days leading up to the attack.[28] On August 14, the Canadians began their attack.

To capture Hill 70 Currie used “bite and hold” tactics combined with a creeping barrage (see Passchendaele and Vimy entries above for definitions) by 200 artillery pieces.[29] This allowed Canadian troops to slowly advance up the hill and construct their defenses. Although the Germans counter attacked over 21 times, using over 15,000 mustard gas shells, grenades, and machine gun and other small arms fire, the Canadians were able to hold the position for seven days.[30] Official Canadian sources state that the fighting at Hill 70 claimed 5,843 Canadian and 20,000 German troops.[31] Although Lens was never captured, Hill 70 would remain in Allied hands until the end of the war. According to General Currie, Hill 70 was the most difficult battle the Canadians had fought to date, including Second Ypres and Vimy Ridge.[32]

To capture Hill 70 Currie used “bite and hold” tactics combined with a creeping barrage (see Passchendaele and Vimy entries above for definitions) by 200 artillery pieces.[29] This allowed Canadian troops to slowly advance up the hill and construct their defenses. Although the Germans counter attacked over 21 times, using over 15,000 mustard gas shells, grenades, and machine gun and other small arms fire, the Canadians were able to hold the position for seven days.[30] Official Canadian sources state that the fighting at Hill 70 claimed 5,843 Canadian and 20,000 German troops.[31] Although Lens was never captured, Hill 70 would remain in Allied hands until the end of the war. According to General Currie, Hill 70 was the most difficult battle the Canadians had fought to date, including Second Ypres and Vimy Ridge.[32]

For the Six Nations, this was a very important battle. After their arrival in England in fall 1916, the 114th “Brocks Ranger’s” Battalion, made up of 300 Six Nations and other First Nations men, was broken up as reinforcements to front line service battalions. Many chose to be transferred to the 107th “Timber Wolf” battalion as it too was made up of mostly First Nations men, some of whom were also from Six Nations.[33] The 107th, along with other construction and pioneer battalions, was ordered to dig trenches, build defenses, and carry supplies for the attack on Hill 70. Although the 107th was made up of 900 men (500 of whom were First Nations), only 600 men participated in the attack.[34] On the first day of the attack, while constructing trenches in no-mans-land under heavy German shelling, the 107th lost 21 men killed in action with 103 men reported as severely wounded.[35] They worked day and night, digging 600 yards of trench a day, which was more than even General Currie expected.[36] Still, the men of the 107th could not keep up with the demand for trenches, which were desperately needed for cover from shelling. Many men who could not find a proper trench found cover in the root cellars of homes that were in the line fire. The men of the 107th, in addition to their work on trench construction, stayed behind to rescue the wounded. While engaged in this service of mercy, they were caught in a German gas attack, which poisoned 88 men.[37] The Timber Wolves performed admirably under fire and received commendations from General Currie and the commander of the 10th Battalion (whose men the 107th had rescued).[38] However, due to the large number of casualties sustained while fighting, the 107th could not continue as a full battalion and was broken up, with its men going to three new engineering battalions in the 1st Canadian Infantry Division.[39]

On the home front, news of casualties came pouring in before the attack began. From August 7 to 16, 1917, The Branford Expositor reported that three Six Nations men of the 107th, had been killed by German fire.[40] Casualty figures from the attack were not reported by The Brantford Expositor until August 29 to September 26, 1917. During this time, nine Six Nations men were reported as casualties. Two were killed in action and seven were wounded.[41] Alongside these Six Nations men were the names of ten men from Brantford and Brant County,[42] making the total Brantford, Brant County, and Six Nations casualties during this campaign 22 men either killed or wounded. Although men from all three communities were casualties, the news that twelve had come from Six Nations hit the community on the Grand River especially hard as it had sent 300 men overseas to fight in the war. Nevertheless, the shared experience of mourning would not only have brought these three communities closer, but would have strengthened the resolve of everyone to contribute to the war effort.

http://www.brantfordexpositor.ca/2013/11/10/the-ww1-diary-of-lloyd-cliff...

The Hundred Days

Alfred Clarke died a soldier's death. Serving with the 54th Battalion, Clarke, 30, of Brantford, was in the thick of the fighting at Amiens when he was shot through the head. He died instantly about two yards from two machine guns brought up by the Prussian Guards.

“We gained a great victory but had to pay the price,” his widow was told in a letter sent home by Clarke's commanding officer. “Your husband met a magnificent death that all soldiers prefer…Be comforted knowing that he died for King, Country and Empire and our dearly beloved wives and children.” [43]

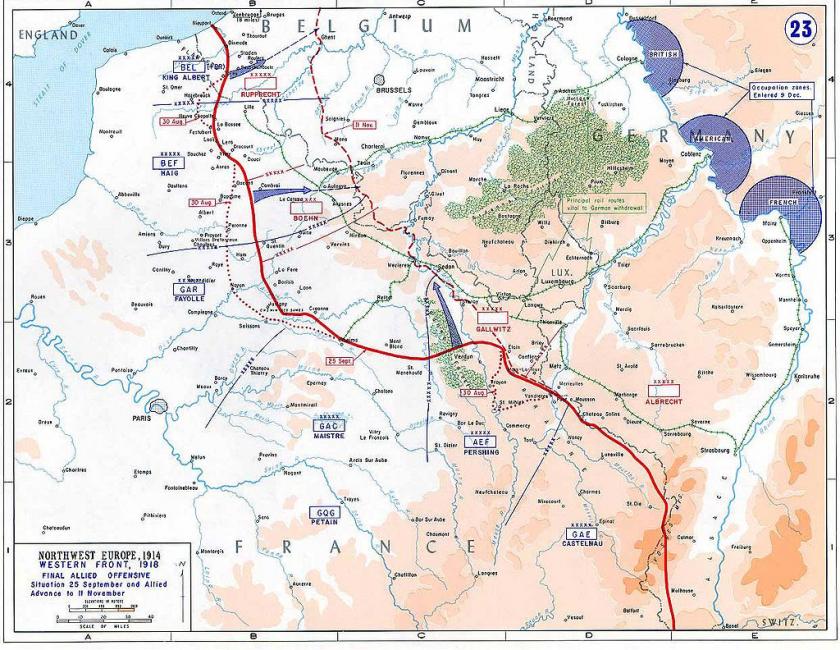

Magnificence and cost. These two themes run through the final stages of the War for Canada’s fighting men. The success of Canadian soldiers, in places like Vimy and Passchendaele, meant that, by 1918, Canadian troops were considered “shock troops”. That is, they were ranked among the British Army’s most capable units and, therefore, were often given the toughest assignments. Never was this more in evidence than during the Hundred Days.[44] This series of engagements marked a return to movement after years of stalemate; it also marked very high casualty rates.

As the website of Veterans Affairs Canada notes “The Canadian Corps’ reputation was [now] such that the mere presence of Canadians on a section of the front would warn the enemy that an attack was coming.”[45] Obviously this was problematic. Therefore, in preparation for the Battle of Amiens, the battle generally acknowledged as the first of the Hundred Days, Canadians were ferried to the familiar ground of the Ypres sector. They were then shuttled out again under cover of darkness to the true starting point for the offensive so as to gain the element of surprise.

The Battle of Amiens began at 4:20 p.m. on August 8. It marked the beginning of the end for Germany as Allied forces made unprecedented progress. On the 8th alone, Canadian troops “advanced 13 kilometres through the German defences, the most successful day of combat for the Allies on the Western Front.” This stunning defeat, on what the Commander of the German Army called its “Black Day” had a number of important impacts. It “shook German faith in the outcome of the war and raised Allied morale.”[46]

Amiens was the first in a series of successful – if costly – battles for Canadian forces. Other engagements normally considered under the umbrella of the Hundred Days include battles at the Drocourt-Queant Line, the Canal du Nord, Cambrai, and Mons (interestingly, the scene of one of the War’s first battles). These battles have prompted a considerable amount of scholarly attention. The consensus has been that the Hundred Days was characterized by tactical successes and significant gains, with a number of experts arguing that this succession of encounters led to victory. More recently, there has been a softening of this view with some historians arguing that there were deficiencies in Canadian planning that contributed to the heavy losses.[47]

Whatever one’s final assessment of the cost vs. reward of the Hundred Days, there is no denying that the Canadian Corps achieved a great deal. During this final period in the War “…more than 100,000 Canadians advanced 130 kilometres and captured approximately 32,000 prisoners and nearly 3,800 artillery pieces, machine guns and mortars.”[48]

[1] “Interview with John Uprichard, 8th Battalion”; available at Library and Archives Canada, “The Second Battle of Ypres” [archived page] http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/first-world-war/interviews/025015-112...

[2] Map taken from Andrew B. Godefroy, “Portrait of a Battalion Commander: Lieutenant-Colonel George Stuart Tuxford at the Second Battle of Ypres, April 1915,” National Defense and the Canadian Armed Forces, http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vo5/no2/history-histoire-eng.asp

[3] See for example John Keegan, An Illustrated History of the First World War (Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 111-118.

[4] Keegan notes that the first use of any type of gas took place in October 1914 at Neuve Chapelle. The agent in this instance was xylil bromide, a type of tear gas but had little impact as the quantities employed were small. In January 1915, larger quantities were used on the Eastern Front, at Bolimov, but low temperatures froze the gas. After these failures, the Germans turned to chlorine, a killing agent that worked by producing fluid in the lungs and essentially drowning the victim (see Keegan, Illustrated History, 176). The British turned to gas themselves in May 1915 at the Battle of Loos.

[5] For an excellent overview, see Canadian War Museum, “Second Ypres,” http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/guerre/second-ypres-e.aspx

[6] John Dixon, Magnificent But Not War: The Battle for Ypres, 1915 (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books, 2009), 49.

[7] B.H. Liddell Hart, A History of the World War, 1914-1918 (London: Faber, 1930), 315, 314.

[8] This interpretation, most forcefully developed by Alan Clark in his 1963 book, The Donkeys suggests that British troops were courageous lions led by incompetent and callous generals.

[9] See Robin Prior and Trevor Wilson, The Somme (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 113.

[10] The memory of the Somme has had a terrible long-lasting effect on Newfoundland. For example, it has meant that Newfoundlanders could never fully enter into the spirit of Dominion/Canada Day. See for example David Macfarlane, The Danger Tree: Memory, War, and the Search for A Family's Past (Toronto: Vintage Books, 2000).

[11] Owen Steele, Diary of Owen Steele, 339–340 MF 147, Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Memorial University of Newfoundland; also available at http://www.heritage.nf.ca/greatwar/articles/somme.html

[12] Major A. Raley, “Beaumont Hamel,” Veteran’s Magazine 1.3 (Sept. 1921), 37-40.

[13] Martin Middlebrook, The First Day on the Somme: July 1, 1916 (London: Penquin Books, 1984), 269.

[14] The Brantford Expositor, May 18, 1917. The letter was originally written on April 26.

[15] For more on the Daiken brothers see “Remembering Vimy Ridge: Twin brothers met mixed fate 90 years ago today,” The Brantford Expositor, April 9, 2007. By Vincent Ball with research by Geoffrey Moyer.

[16] Pierre Berton, Vimy (Toronto: Anchor Canada, 2001), 293.

[17] A prime example of this is Geoff Hayes et al. eds., Vimy Ridge: A Canadian Reassessment (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2010).

[18] Gary Sheffield, “Vimy Ridge and the Battle of Arras: A British Perspective,” in Hayes et al. eds. Vimy Ridge, 15.

[19] For more about Van Fleet, see “Valour in the Belgian Mud,” The Brantford Expositor, Nov. 10, 2007 by Vincent Ball with research by Geoffrey Moyer.

[20] Keegan, Illustrated History, 334-335.

[21] Ibid., 337, 339.

[22] Ibid., 339, 342.

[23] Ibid., 334-335.

[24] Bob Gordon and Thomas Gordon, “The Battle of Hill 70, August 15-22, 1917: In the Seesaw Battles of Attrition on the Western Front, the Cost in Lives was Steep--Often just a Few Hundred Meters of Captured Ground,” Esprit de Corps (July 2011) and Dan Jenkins, “Fight for Hill 70, 15 August 1917,” Esprit de Corps (Mar. 2000).

[25] Tim Cook, Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting the Great War, 1917-1918 (Toronto: Viking Canada, 2008), 265.

[26] Cook, Shock Troops, 266.

[27] Dan Jenkins, “Fight for Hill 70, 15 August 1917”.

[28] Cook, Shock Troops, 266, 268; Bob Gordon and Thomas Gordon “The Battle of Hill 70”.

[29] Bob Gordon and Thomas Gordon, “The Battle of Hill 70”.

[30] Cook, Shock Troops, 293, 295; Bob Gordon and Thomas Gordon “The Battle of Hill 70”.

[31] Bob Gordon and Thomas Gordon, “The Battle of Hill 70”.and Dan Jenkins, “Fight for Hill 70, 15 August 1917.”

[32] Dan Jenkins, “Fight for Hill 70, 15 August 1917”.

[33] Steven A. Bell, “The 107th "Timber Wolf" Battalion at Hill 70,” Canadian Military History 5, 1 (1996): 73.

[34] Bell, 73, 76.

[35] Ibid., 76.

[36] Ibid., 76, 77.

[37] Ibid., 76, 77.

[38] Ibid., 77.

[39] Ibid., 78.

[40] The Brantford Expositor, August 7, August 10 and August 16, 1917.

[41] The Brantford Expositor, August 29, September 1, September 13, September 15, and September 26, 1917.

[42] The Brantford Expositor, August 10, August 29, and September 1, 1917.

[43] The Brantford Expositor, December 6, 1918

[44] For more on the Hundred Days, see Vincent Ball with Geoffrey Moyer, “The Supreme Sacrifice” The Brantford Expositor, Nov. 8, 2008.

[45] Veterans Affairs Canada, “The Last Hundred Days”; available at https://www.veterans.gc.ca/pdf/publications/canada-remembers/FWW_Last_10...

[46] Canadian War Museum, “Canada and the First World War”; available at http://www.warmuseum.ca/cwm/exhibitions/guerre/amiens-e.aspx

[47] For the traditional view of the Hundred Days, see Terry Copp, “The Military Effort 1914-1918,” in Canada and the First World War, David Mackenzie (ed.) (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 56. For a more critical evaluation, see Tim Cook, Shock Troops: Canadians Fighting in the Great War 1917-1918 (Toronto: Penguin Group, 2008), 498 or Tim Cook, The Madman and the Butcher: The Sensational Wars of Sam Hughes and General Arthur Currie (Toronto: Penguin Group, 2010). A very useful brief overview of the various schools of thought on the Hundred Days can be found in Ryan Goldsworthy, “Measuring the Success of Canada's Wars: The Hundred Days Offensive As A Case Study”; available at http://www.journal.forces.gc.ca/vol13/no2/page46-eng.asp

[48] Veterans Affairs Canada, “The Last Hundred Days”; available at: http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/history/first-world-war/fact_s...